Brief History

1. Auburn and Pennsylvania Systems: Contradictions in Reform Efforts

Some of the first real penitentiaries in the world were developed in the United States. These institutions, specifically the Auburn and Pennsylvania systems, were efforts to reform a system of punishment their supporters saw to be brutal and essentially pointless. In place of the dungeons and corporal punishment that characterized U.S. justice before these institutions’ development, they would be places of the true reform of the prisoner, focusing on quiet, in order to give the offender time to contemplate his crime, and work, to give the offender meaning and bring him closer to God. For more on this history, see Rubin 2021. These institutions, along with similar emerging institutions in Great Britain and France and the logic and rational of work, salvation, and reform that accompanied them, spread across the globe as other countries imported their designs and rational, repurposing them to local conditions and the needs of local elites for (often racialized) social control (see Nikpor 2024 for Iran, or Salvatore and Aguirre 1996 for Latin America).

But the development of the Auburn and Pennsylvania systems in the 19th century must also be understood against the backdrop of slavery's influence on labor exploitation and social hierarchies. The Auburn system's emphasis on disciplined labor mirrored the coercive work regimes enforced on plantations, perpetuating a cycle of forced labor and control reminiscent of slavery. Similarly, the Pennsylvania system's strict isolation and silence echoed the dehumanizing aspects of slavery, raising questions about the continuity of oppressive practices under the guise of reformative measures.

Beyond these more conceptual concerns, these initial penitentiaries produced the logic and infrastructure that gives us the system of racialized mass incarceration in the United States today, which has proven especially adept at incorporating efforts at reform into its broader project of the coercion and management of racialized and poor populations.

These questions persist regarding reform movements today and the balance to strike (if any) between remaking the prison system in a more humane form and doing away with it altogether, searching instead for structural answers to the structural problems which produce the prison and crime.

2. Convict Leasing and Chain Gangs

After the Civil War and the abolition of slavery, southern states adopted convict leasing programs. This allowed them to maintain control over Black populations and exploit convict labor. The 13th Amendment to the Constitution, ratified in December of 1865 and which abolished slavery, carved out exceptions for the incarcerated to the freedom Black Americans had seized: “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” This system allowed private companies and individuals to lease convicts from state prisons for labor, often under brutal and inhumane conditions. The system of chain gangs, where groups of prisoners were chained together and forced to perform hard labor still exists in many places today. It has been reappropriated to other carceral systems, like immigration detention, where administrators or elected officials often use it simultaneously as media spectacle and revenue source. For an extensive overview of convict leasing and its relationship to slavery and to continuing racial inequalities for Black Americans, see Childs 2015. For a story close to Atlanta and to Emory University, see the history of Joel Hurt, often considered one of the city fathers of Atlanta and related by marriage to the namesake of this library, and his exploitation of Black convict labor in the coal mines he owned in Northern Georgia.

3. 20th Century: Mass Incarceration and Social Injustice

The 20th century witnessed the culmination of historical legacies of structural racism and class inequality as mass incarceration became a central feature of the American criminal justice system. The "War on Drugs" policies disproportionately targeted communities of color, continuing a pattern of racial discrimination and social control reminiscent of slavery-era practices, and simultaneously incarcerating poor Whites in huge numbers. The privatization of some prisons further commodified incarceration, turning human beings into profit-generating assets, similar to what we see under convict leasing but accomplished much differently. These combined policies produced potentially the most extreme program of incarceration and forced labor the world has known since the institution of the Atlantic Slave Trade and one of the highest rates of incarceration in the world (only recently having been displaced by El Salvador, which has borrowed a great deal of the U.S. approach to crime and punishment, as well as criminalization through media spectacle). For more on the rapid expansion of prisons through the War on Drugs, see Bobo and Thompson 2015 and the later weeks of the AAIHS Prison Abolition Syllabus.

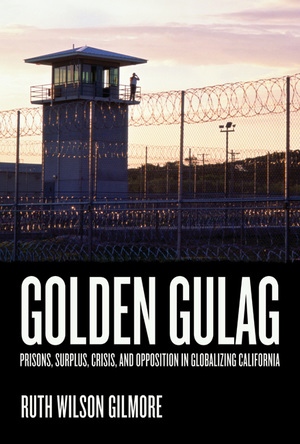

Ruth Wilson Gilmore’s landmark work on the rapid expansion of the prison system during this era and the simultaneous reduction of funds for social programs in California, Golden Gulag, is key to understanding how this extreme program came about. Aside from Foucault’s Discipline and Punish, it is probably the most cited in the study of U.S. prisons. Her dialectical analysis investigates the geography and space of prisons from a structural and marxist perspective. She is less concerned with the spaces of individual prison cells (see Guenther for an investigation of the physical and psychological space of the cell and solitary confinement) and more those of carcerality and abolition -the physical, social, and economic geographies of prisons and anti-prison and abolitionist movements. Gilmore’s dialectic analysis in Gulag, along with others in the field, moved the study of mass incarceration away from Foucault’s more abstract analysis and towards material questions of economy, class, and race, and the structural elements of U.S. economies that produce and exploit. For more on how this was a bipartisan project rather than one driven exclusively by conservative elements of the polity, see Naomi Paik's Rightlessness, which investigates the role of New Deal reformers and white liberal ideas about race in the development of modern racialized mass incarceration. For more on the relationship between urban space and the carceral state, see Thompson and Murch 2015.

4. The Contemporary: Reform and Abolition

In the contemporary context, efforts to reform the criminal justice system must confront the enduring influence of slavery on incarceration practices and the constance of structural racial inequality in the U.S. justice system and the cultural sphere. Addressing systemic racism, advocating for restorative justice, and promoting equitable sentencing policies are essential steps towards dismantling the historical legacies of slavery within the modern prison system. Moreover, recognizing the intersectionality of race, class, and incarceration is crucial for developing comprehensive reforms that prioritize rehabilitation, social justice, and community well-being. For more on modern efforts at prison abolition, see the later weeks in the African American Intellectual History Society’s Prison Abolition Syllabus, Angela Davis’ body of work, Ruth Wilson Gilmore, and many others.

The history of prisons in the United States is embedded in the legacy of slavery, racial segregation, and modernization. Its open brutality and persistent structural influence on global modern mass incarceration undermines more abstract conceptualizations of the prison, as well as reform movements which take an individualized approach. It shows that, contrary to Foucault’s proposal that the target for disciplinary systems after the 1700s became the prisoner’s soul and not his body, in the Americas (and by implication in many other parts of the world) the body, in this case, a heavily racialized one, is still that system’s target. Furthermore, especially thinking with Ruth Wilson Gilmore and others, this history in the United States shows that the structural and economic forces that the prison system reproduces and represents -in this case capitalism, institutional racism and the warehousing and management of lower economic classes- must be considered in any critical analysis of punishment and racialized mass incarceration, whether in the United States or elsewhere.

Texts

-

Rightlessness by

ISBN: 9781469626314Publication Date: 2016-04-11In this bold book, A. Naomi Paik grapples with the history of U.S. prison camps that have confined people outside the boundaries of legal and civil rights. Removed from the social and political communities that would guarantee fundamental legal protections, these detainees are effectively rightless, stripped of the right even to have rights. Rightless people thus expose an essential paradox: while the United States purports to champion inalienable rights at home and internationally, it has built its global power in part by creating a regime of imprisonment that places certain populations perceived as threats beyond rights. The United States' status as the guardian of rights coincides with, indeed depends on, its creation of rightlessness. Yet rightless people are not silent. Drawing from an expansive testimonial archive of legal proceedings, truth commission records, poetry, and experimental video, Paik shows how rightless people use their imprisonment to protest U.S. state violence. She examines demands for redress by Japanese Americans interned during World War II, testimonies of HIV-positive Haitian refugees detained at Guantanamo in the early 1990s, and appeals by Guantanamo's enemy combatants from the War on Terror. In doing so, she reveals a powerful ongoing contest over the nature and meaning of the law, over civil liberties and global human rights, and over the power of the state in people's lives. -

Violence Work by

ISBN: 9781478002024Publication Date: 2018-08-02In Violence Work Micol Seigel offers a new theorization of the quintessential incarnation of state power: the police. Foregrounding the interdependence of policing, the state, and global capital, Seigel redefines policing as "violence work," showing how it is shaped by its role of channeling state violence. She traces this dynamic by examining the formation, demise, and aftermath of the U.S. State Department's Office of Public Safety (OPS), which between 1962 and 1974 specialized in training police forces internationally. Officially a civilian agency, the OPS grew and operated in military and counterinsurgency realms in ways that transgressed the borders that are meant to contain the police within civilian, public, and local spheres. Tracing the career paths of OPS agents after their agency closed, Seigel shows how police practices writ large are rooted in violence--especially against people of color, the poor, and working people--and how understanding police as a civilian, public, and local institution legitimizes state violence while preserving the myth of state benevolence. -

Presumed criminal : black youth and the justice system in postwar New York by

ISBN: 1479812692Publication Date: 2019A startling examination of the deliberate criminalization of black youths from the 1930s totodayA stark disparity exists between black and white youth experiences in the justice system today. Black youths are perceived to be older and less innocent than their white peers. When it comes to incarceration, race trumps class, and even as black youths articulate their own experiences with carceral authorities, many Americans remain surprised by the inequalities they continue to endure. In this revealing book, Carl Suddler brings to light a much longer history of the policies and strategies that tethered the lives of black youths to the justice system indefinitely.The criminalization of black youth is inseparable from its racialized origins. In the mid-twentieth century, the United States justice system began to focus on punishment, rather than rehabilitation. By the time the federal government began to address the issue of juvenile delinquency, the juvenile justice system shifted its priorities from saving delinquent youth to purely controlling crime, and black teens bore the brunt of the transition.In New York City, increased state surveillance of predominantly black communities compounded arrest rates during the post-World War II period, providing justification for tough-on-crime policies. Questionable police practices, like stop-and-frisk, combined with media sensationalism, cemented the belief that black youth were the primary cause for concern. Even before the War on Crime, the stakes were clear: race would continue to be the crucial determinant in American notions of crime and delinquency, and black youths condemned with a stigma of criminality would continue to confront the overwhelming power of the state. -

Executing Freedom by

ISBN: 9780226066691Publication Date: 2016-11-18In the mid-1990s, as public trust in big government was near an all-time low, 80% of Americans told Gallup that they supported the death penalty. Why did people who didn't trust government to regulate the economy or provide daily services nonetheless believe that it should have the power to put its citizens to death? That question is at the heart of Executing Freedom, a powerful, wide-ranging examination of the place of the death penalty in American culture and how it has changed over the years. Drawing on an array of sources, including congressional hearings and campaign speeches, true crime classics like In Cold Blood, and films like Dead Man Walking, Daniel LaChance shows how attitudes toward the death penalty have reflected broader shifts in Americans' thinking about the relationship between the individual and the state. Emerging from the height of 1970s disillusion, the simplicity and moral power of the death penalty became a potent symbol for many Americans of what government could do--and LaChance argues, fascinatingly, that it's the very failure of capital punishment to live up to that mythology that could prove its eventual undoing in the United States. -

Pacifying the Homeland by

ISBN: 0520971345Publication Date: 2019-08-06The United States has poured over a billion dollars into a network of interagency intelligence centers called "fusion centers." These centers were ostensibly set up to prevent terrorism, but politicians, the press, and policy advocates have criticized them for failing on this account. So why do these security systems persist? Pacifying the Homeland travels inside the secret world of intelligence fusion, looks beyond the apparent failure of fusion centers, and reveals a broader shift away from mass incarceration and toward a more surveillance- and police-intensive system of social regulation. Provided with unprecedented access to domestic intelligence centers, Brendan McQuade uncovers how the institutionalization of intelligence fusion enables decarceration without fully addressing the underlying social problems at the root of mass incarceration. The result is a startling analysis that contributes to the debates on surveillance, mass incarceration, and policing and challenges readers to see surveillance, policing, mass incarceration, and the security state in an entirely new light. -

Decarcerating Disability by

ISBN: 1452963495Publication Date: 2020-05-19This vital addition to carceral, prison, and disability studies draws important new links between deinstitutionalization and decarceration Prison abolition and decarceration are increasingly debated, but it is often without taking into account the largest exodus of people from carceral facilities in the twentieth century: the closure of disability institutions and psychiatric hospitals. Decarcerating Disability provides a much-needed corrective, combining a genealogy of deinstitutionalization with critiques of the current prison system. Liat Ben-Moshe provides groundbreaking case studies that show how abolition is not an unattainable goal but rather a reality, and how it plays out in different arenas of incarceration--antipsychiatry, the field of intellectual disabilities, and the fight against the prison-industrial complex. Ben-Moshe discusses a range of topics, including why deinstitutionalization is often wrongly blamed for the rise in incarceration; who resists decarceration and deinstitutionalization, and the coalitions opposing such resistance; and how understanding deinstitutionalization as a form of residential integration makes visible intersections with racial desegregation. By connecting deinstitutionalization with prison abolition, Decarcerating Disability also illuminates some of the limitations of disability rights and inclusion discourses, as well as tactics such as litigation, in securing freedom. Decarcerating Disability's rich analysis of lived experience, history, and culture helps to chart a way out of a failing system of incarceration.

-

American Prison Newspapers, 1800s-present: Voices from the InsideCollection of newspapers produced in U.S. prisons by prisoners, 1800s-present.

-

Captive Nation by

ISBN: 9781469618241Publication Date: 2014-11-14In this pathbreaking book, Dan Berger offers a bold reconsideration of twentieth century black activism, the prison system, and the origins of mass incarceration. Throughout the civil rights era, black activists thrust the prison into public view, turning prisoners into symbols of racial oppression while arguing that confinement was an inescapable part of black life in the United States. Black prisoners became global political icons at a time when notions of race and nation were in flux. Showing that the prison was a central focus of the black radical imagination from the 1950s through the 1980s, Berger traces the dynamic and dramatic history of this political struggle. The prison shaped the rise and spread of black activism, from civil rights demonstrators willfully risking arrests to the many current and former prisoners that built or joined organizations such as the Black Panther Party. Grounded in extensive research, Berger engagingly demonstrates that such organizing made prison walls porous and influenced generations of activists that followed. -

The Culture of Punishment by

ISBN: 9780814799994Publication Date: 2009-10-15America is the most punitive nation in the world, incarcerating more than 2.3 million people--or one in 136 of its residents. Against the backdrop of this unprecedented mass imprisonment, punishment permeates everyday life, carrying with it complex cultural meanings. In The Culture of Punishment, Michelle Brown goes beyond prison gates and into the routine and popular engagements of everyday life, showing that those of us most distanced from the practice of punishment tend to be particularly harsh in our judgments. The Culture of Punishment takes readers on a tour of the sites where culture and punishment meet--television shows, movies, prison tourism, and post 9/11 new war prisons--demonstrating that because incarceration affects people along distinct race and class lines, it is only a privileged group of citizens who are removed from the experience of incarceration. These penal spectators, who often sanction the infliction of pain from a distance, risk overlooking the reasons for democratic oversight of the project of punishment and, more broadly, justifications for the prohibition of pain. -

Carceral Spaces by

ISBN: 1472400038Publication Date: 2013-04-09This book draws together the work of a new community of scholars with a growing interest in carceral geography. It combines work by geographers on 'mainstream' penal establishments where people are incarcerated by the prevailing legal system, with geographers' recent work on migrant detention centres. -

Carceral Logics by

ISBN: 9781108919210Publication Date: 2022-04-09Carceral logics permeate our thinking about humans and nonhumans. We imagine that greater punishment will reduce crime and make society safer. We hope that more convictions and policing for animal crimes will keep animals safe and elevate their social status. The dominant approach to human-animal relations is governed by an unjust imbalance of power that subordinates or ignores the interest nonhumans have in freedom. In this volume Lori Gruen and Justin Marceau invite experts to provide insights into the complicated intersection of issues that arise in thinking about animal law, violence, mass incarceration, and social change. Advocates for enhancing the legal status of animals could learn a great deal from the history and successes (and failures) of other social movements. Likewise, social change lawyers, as well as animal advocates, might learn lessons from each other about the interconnections of oppression as they work to achieve liberation for all. This title is also available as Open Access on Cambridge Core. -

Badges Without Borders by

ISBN: 0520968336Publication Date: 2019-10-15From the Cold War through today, the U.S. has quietly assisted dozens of regimes around the world in suppressing civil unrest and securing the conditions for the smooth operation of capitalism. Casting a new light on American empire, Badges Without Borders shows, for the first time, that the very same people charged with global counterinsurgency also militarized American policing at home. In this groundbreaking exposé, Stuart Schrader shows how the United States projected imperial power overseas through police training and technical assistance--and how this effort reverberated to shape the policing of city streets at home. Examining diverse records, from recently declassified national security and intelligence materials to police textbooks and professional magazines, Schrader reveals how U.S. police leaders envisioned the beat to be as wide as the globe and worked to put everyday policing at the core of the Cold War project of counterinsurgency. A "smoking gun" book, Badges without Borders offers a new account of the War on Crime, "law and order" politics, and global counterinsurgency, revealing the connections between foreign and domestic racial control. -

Solitary Confinement by

ISBN: 0816686246Publication Date: 2013-08-01rolonged solitary confinement has become a widespread and standard practice in U.S. prisons—even though it consistently drives healthy prisoners insane, makes the mentally ill sicker, and, according to the testimony of prisoners, threatens to reduce life to a living death. In this profoundly important and original book, Lisa Guenther examines the death-in-life experience of solitary confinement in America from the early nineteenth century to today’s supermax prisons. Documenting how solitary confinement undermines prisoners’ sense of identity and their ability to understand the world, Guenther demonstrates the real effects of forcibly isolating a person for weeks, months, or years.

Drawing on the testimony of prisoners and the work of philosophers and social activists from Edmund Husserl and Maurice Merleau-Ponty to Frantz Fanon and Angela Davis, the author defines solitary confinement as a kind of social death. It argues that isolation exposes the relational structure of being by showing what happens when that structure is abused—when prisoners are deprived of the concrete relations with others on which our existence as sense-making creatures depends. Solitary confinement is beyond a form of racial or political violence; it is an assault on being.

A searing and unforgettable indictment, Solitary Confinement reveals what the devastation wrought by the torture of solitary confinement tells us about what it means to be human—and why humanity is so often destroyed when we separate prisoners from all other people.

Source: Publisher -

Way down in the Hole by

ISBN: 9781978823785Publication Date: 2022-10-14Based on ethnographic observations and interviews with prisoners, correctional officers, and civilian staff conducted in solitary confinement units, Way Down in the Hole explores the myriad ways in which daily, intimate interactions between those locked up twenty-four hours a day and the correctional officers charged with their care, custody, and control produce and reproduce hegemonic racial ideologies. Smith and Hattery explore the outcome of building prisons in rural, economically depressed communities, staffing them with white people who live in and around these communities, filling them with Black and brown bodies from urban areas and then designing the structure of solitary confinement units such that the most private, intimate daily bodily functions take place in very public ways. Under these conditions, it shouldn't be surprising, but is rarely considered, that such daily interactions produce and reproduce white racial resentment among many correctional officers and fuel the racialized tensions that prisoners often describe as the worst forms of dehumanization. Way Down in the Hole concludes with recommendations for reducing the use of solitary confinement, reforming its use in a limited context, and most importantly, creating an environment in which prisoners and staff co-exist in ways that recognize their individual humanity and reduce rather than reproduce racial antagonisms and racial resentment. Way Down the Hole Video 1 (https://youtu.be/UuAB63fhge0) Way Down the Hole Video 2 (https://youtu.be/TwEuw1cTrcQ) Way Down the Hole Video 3 (https://youtu.be/bOcBv_UnHIs) Way Down the Hole Video 4 (https://youtu.be/cx_l1S8D77c) -

Golden Gulag

by

ISBN: 0520938038Publication Date: 2007-01-08Since 1980, the number of people in U.S. prisons has increased more than 450%. Despite a crime rate that has been falling steadily for decades, California has led the way in this explosion, with what a state analyst called "the biggest prison building project in the history of the world." Golden Gulag provides the first detailed explanation for that buildup by looking at how political and economic forces, ranging from global to local, conjoined to produce the prison boom. In an informed and impassioned account, Ruth Wilson Gilmore examines this issue through statewide, rural, and urban perspectives to explain how the expansion developed from surpluses of finance capital, labor, land, and state capacity. Detailing crises that hit California's economy with particular ferocity, she argues that defeats of radical struggles, weakening of labor, and shifting patterns of capital investment have been key conditions for prison growth. The results--a vast and expensive prison system, a huge number of incarcerated young people of color, and the increase in punitive justice such as the "three strikes" law--pose profound and troubling questions for the future of California, the United States, and the world. Golden Gulag provides a rich context for this complex dilemma, and at the same time challenges many cherished assumptions about who benefits and who suffers from the state's commitment to prison expansion.

Golden Gulag

by

ISBN: 0520938038Publication Date: 2007-01-08Since 1980, the number of people in U.S. prisons has increased more than 450%. Despite a crime rate that has been falling steadily for decades, California has led the way in this explosion, with what a state analyst called "the biggest prison building project in the history of the world." Golden Gulag provides the first detailed explanation for that buildup by looking at how political and economic forces, ranging from global to local, conjoined to produce the prison boom. In an informed and impassioned account, Ruth Wilson Gilmore examines this issue through statewide, rural, and urban perspectives to explain how the expansion developed from surpluses of finance capital, labor, land, and state capacity. Detailing crises that hit California's economy with particular ferocity, she argues that defeats of radical struggles, weakening of labor, and shifting patterns of capital investment have been key conditions for prison growth. The results--a vast and expensive prison system, a huge number of incarcerated young people of color, and the increase in punitive justice such as the "three strikes" law--pose profound and troubling questions for the future of California, the United States, and the world. Golden Gulag provides a rich context for this complex dilemma, and at the same time challenges many cherished assumptions about who benefits and who suffers from the state's commitment to prison expansion. -

Paths to Prison by

ISBN: 9781941332665Publication Date: 2020-09-07As Angela Y. Davis has proposed, the "path to prison," which so disproportionately affects communities of color, is most acutely guided by the conditions of daily life. Architecture, then, as fundamental to shaping these conditions of civil existence, must be interrogated for its involvement along this diffuse and mobile path. Paths to Prison: On the Architectures of Carcerality aims to expand the ways the built environment's relationship to and participation in the carceral state is understood in architecture. The collected essays in this book implicate architecture in the more longstanding and pervasive legacies of racialized coercion in the United States--and follow the premise that to understand how the prison enacts its violence in the present one must shift the epistemological frame elsewhere: to places, discourses, and narratives assumed to be outside of the sphere of incarceration. Paths to Prison: On the Architectures of Carcerality offers not a fixed or inexorable account of how things are but rather a set of starting points and methodologies for reevaluating the architecture of carceral society and for undoing it altogether. With contributions by Adrienne Brown, Stephen Dillon, Jarrett M. Drake, Sable Elyse Smith, James Graham, Leslie Lodwick, Dylan Rodríguez, Anne Spice, Brett Story, Jasmine Syedullah, Mabel O. Wilson, and Wendy L. Wright. -

Time in the Shadows by

ISBN: 0804783977Publication Date: 2012-11-01Time in the Shadows examines the counterinsurgencies of our time, tracing their ancestry, to offer a critical reading of the mechanisms by which today's counterinsurgents--foremost the United States and Israel--reproduce illiberal regimes of domination while noisily declaring their liberal intent to liberate and improve. Detention and confinement-of both combatants and large groups of civilians-have become fixtures of asymmetric wars over the course of the last century. Counterinsurgency theoreticians and practitioners explain this dizzying rise of detention camps, internment centers, and enclavisation by arguing that such actions ""protect"" populations. In this book, Laleh Khalili counters these arguments, telling the story of how this proliferation of concentration camps, strategic hamlets, ""security walls,"" and offshore prisons has come to be. -

Incarcerating the Crisis by

ISBN: 0520957687Publication Date: 2016-04-18The United States currently has the largest prison population on the planet. Over the last four decades, structural unemployment, concentrated urban poverty, and mass homelessness have also become permanent features of the political economy. These developments are without historical precedent, but not without historical explanation. In this searing critique, Jordan T. Camp traces the rise of the neoliberal carceral state through a series of turning points in U.S. history including the Watts insurrection in 1965, the Detroit rebellion in 1967, the Attica uprising in 1971, the Los Angeles revolt in 1992, and events in post-Katrina New Orleans in 2005. Incarcerating the Crisis argues that these dramatic events coincided with the emergence of neoliberal capitalism and the state's attempts to crush radical social movements. Through an examination of the poetic visions of social movements--including those by James Baldwin, Marvin Gaye, June Jordan, José Ramírez, and Sunni Patterson--it also suggests that alternative outcomes have been and continue to be possible. -

From Asylum to Prison by

ISBN: 9781469640631Publication Date: 2018-10-08To many, asylums are a relic of a bygone era. State governments took steps between 1950 and 1990 to minimize the involuntary confinement of people in psychiatric hospitals, and many mental health facilities closed down. Yet, as Anne Parsons reveals, the asylum did not die during deinstitutionalization. Instead, it returned in the modern prison industrial complex as the government shifted to a more punitive, institutional approach to social deviance. Focusing on Pennsylvania, the state that ran one of the largest mental health systems in the country, Parsons tracks how the lack of community-based services, a fear-based politics around mental illness, and the economics of institutions meant that closing mental hospitals fed a cycle of incarceration that became an epidemic. This groundbreaking book recasts the political narrative of the late twentieth century, as Parsons charts how the politics of mass incarceration shaped the deinstitutionalization of psychiatric hospitals and mental health policy making. In doing so, she offers critical insight into how the prison took the place of the asylum in crucial ways, shaping the rise of the prison industrial complex. -

Shadows of Doubt by

ISBN: 0674240162Publication Date: 2019-04-15Crime and punishment occur under extreme uncertainty. Offenders, victims, police, judges, and jurors make high-stakes decisions with limited information under severe time pressure. With compelling stories and data on how people act and react, O'Flaherty and Sethi reveal the extent to which we rely on stereotypes as shortcuts in our decision making. -

From the War on Poverty to the War on Crime by

ISBN: 9780674969223Publication Date: 2016-05-02Co-Winner of the Thomas J. Wilson Memorial Prize A New York Times Notable Book of the Year A New York Times Book Review Editors' Choice A Wall Street Journal Favorite Book of the Year A Choice Outstanding Academic Title of the Year A Publishers Weekly Favorite Book of the Year In the United States today, one in every thirty-one adults is under some form of penal control, including one in eleven African American men. How did the "land of the free" become the home of the world's largest prison system? Challenging the belief that America's prison problem originated with the Reagan administration's War on Drugs, Elizabeth Hinton traces the rise of mass incarceration to an ironic source: the social welfare programs of Lyndon Johnson's Great Society at the height of the civil rights era. "An extraordinary and important new book." --Jill Lepore, New Yorker "Hinton's book is more than an argument; it is a revelation...There are moments that will make your skin crawl...This is history, but the implications for today are striking. Readers will learn how the militarization of the police that we've witnessed in Ferguson and elsewhere had roots in the 1960s." --Imani Perry, New York Times Book Review -

City of Inmates by

ISBN: 1469659190Publication Date: 2020-02-01Los Angeles incarcerates more people than any other city in the United States, which imprisons more people than any other nation on Earth. This book explains how the City of Angels became the capital city of the world's leading incarcerator. Marshaling more than two centuries of evidence, historian Kelly Lytle Hernandez unmasks how histories of native elimination, immigrant exclusion, and black disappearance drove the rise of incarceration in Los Angeles. In this telling, which spans from the Spanish colonial era to the outbreak of the 1965 Watts Rebellion, Hernandez documents the persistent historical bond between the racial fantasies of conquest, namely its settler colonial form, and the eliminatory capacities of incarceration. But City of Inmates is also a chronicle of resilience and rebellion, documenting how targeted peoples and communities have always fought back. They busted out of jail, forced Supreme Court rulings, advanced revolution across bars and borders, and, as in the summer of 1965, set fire to the belly of the city. With these acts those who fought the rise of incarceration in Los Angeles altered the course of history in the city, the borderlands, and beyond. This book recounts how the dynamics of conquest met deep reservoirs of rebellion as Los Angeles became the City of Inmates, the nation's carceral core. It is a story that is far from over. -

Social Death by

ISBN: 0814723756Publication Date: 2012-11-12Winner of the 2013 John Hope Franklin Book Prize presented by the American Studies Association A necessary read that demonstrates the ways in which certain people are devalued without attention to social contexts Social Death tackles one of the core paradoxes of social justice struggles and scholarship--that the battle to end oppression shares the moral grammar that structures exploitation and sanctions state violence. Lisa Marie Cacho forcefully argues that the demands for personhood for those who, in the eyes of society, have little value, depend on capitalist and heteropatriarchal measures of worth. With poignant case studies, Cacho illustrates that our very understanding of personhood is premised upon the unchallenged devaluation of criminalized populations of color. Hence, the reliance of rights-based politics on notions of who is and is not a deserving member of society inadvertently replicates the logic that creates and normalizes states of social and literal death. Her understanding of inalienable rights and personhood provides us the much-needed comparative analytical and ethical tools to understand the racialized and nationalized tensions between racial groups. Driven by a radical, relentless critique, Social Death challenges us to imagine a heretofore "unthinkable" politics and ethics that do not rest on neoliberal arguments about worth, but rather emerge from the insurgent experiences of those negated persons who do not live by the norms that determine the productive, patriotic, law abiding, and family-oriented subject. -

Slaves of the State by

ISBN: 9780816692415Publication Date: 2015-02-27The Thirteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution, passed in 1865, has long been viewed as a definitive break with the nation's past by abolishing slavery and ushering in an inexorable march toward black freedom. Slaves of the State presents a stunning counterhistory to this linear narrative of racial, social, and legal progress in America. Dennis Childs argues that the incarceration of black people and other historically repressed groups in chain gangs, peon camps, prison plantations, and penitentiaries represents a ghostly perpetuation of chattel slavery. He exposes how the Thirteenth Amendment's exception clause--allowing for enslavement as "punishment for a crime"--has inaugurated forms of racial capitalist misogynist incarceration that serve as haunting returns of conditions Africans endured in the barracoons and slave ship holds of the Middle Passage, on plantations, and in chattel slavery. Childs seeks out the historically muted voices of those entombed within terrorizing spaces such as the chain gang rolling cage and the modern solitary confinement cell, engaging the writings of Toni Morrison and Chester Himes as well as a broad range of archival materials, including landmark court cases, prison songs, and testimonies, reaching back to the birth of modern slave plantations such as Louisiana's "Angola" penitentiary. Slaves of the State paves the way for a new understanding of chattel slavery as a continuing social reality of U.S. empire--one resting at the very foundation of today's prison industrial complex that now holds more than 2.3 million people within the country's jails, prisons, and immigrant detention centers. -

Building the Prison State by

ISBN: 9780226520964Publication Date: 2018-02-19The United States incarcerates more people per capita than any other industrialized nation in the world--about 1 in 100 adults, or more than 2 million people--while national spending on prisons has catapulted 400 percent. Given the vast racial disparities in incarceration, the prison system also reinforces race and class divisions. How and why did we become the world's leading jailer? And what can we, as a society, do about it? Reframing the story of mass incarceration, Heather Schoenfeld illustrates how the unfinished task of full equality for African Americans led to a series of policy choices that expanded the government's power to punish, even as they were designed to protect individuals from arbitrary state violence. Examining civil rights protests, prison condition lawsuits, sentencing reforms, the War on Drugs, and the rise of conservative Tea Party politics, Schoenfeld explains why politicians veered from skepticism of prisons to an embrace of incarceration as the appropriate response to crime. To reduce the number of people behind bars, Schoenfeld argues that we must transform the political incentives for imprisonment and develop a new ideological basis for punishment. -

Forced Passages by

ISBN: 0816645604Publication Date: 2006-01-01More than two million people are currently imprisoned in the United States, and the nation’s incarceration rate is now the highest in the world. The dramatic rise and consolidation of America’s prison system has devastated lives and communities. But it has also transformed prisons into primary sites of radical political discourse and resistance as they have become home to a growing number of writers, activists, poets, educators, and other intellectuals who offer radical critiques of American society both within and beyond the prison walls. In Forced Passages, Dylan Rodríguez argues that the cultural production of such imprisoned intellectuals as Mumia Abu-Jamal, Angela Davis, Leonard Peltier, George Jackson, José Solis Jordan, Ramsey Muniz, Viet Mike Ngo, and Marilyn Buck should be understood as a social and intellectual movement in and of itself, unique in context and substance. Rodríguez engages with a wide range of texts, including correspondence, memoirs, essays, poetry, communiqués, visual art, and legal writing, drawing on published works by widely recognized figures and by individuals outside the public’s field of political vision or concern. Throughout, Rodríguez focuses on the conditions under which imprisoned intellectuals live and work, and he explores how incarceration shapes the ways in which insurgent knowledge is created, disseminated, and received. More than a series of close readings of prison literature, Forced Passages identifies and traces the discrete lineage of radical prison thought since the 1970s, one formed by the logic of state violence and by the endemic racism of the criminal justice system. Dylan Rodríguez is assistant professor of ethnic studies at the University of California, Riverside. -

The Deviant Prison

by

ISBN: 9781108754095Publication Date: 2021-01-12Early nineteenth-century American prisons followed one of two dominant models: the Auburn system, in which prisoners performed factory-style labor by day and were placed in solitary confinement at night, and the Pennsylvania system, where prisoners faced 24-hour solitary confinement for the duration of their sentences. By the close of the Civil War, the majority of prisons in the United States had adopted the Auburn system - the only exception was Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary, making it the subject of much criticism and a fascinating outlier. Using the Eastern State Penitentiary as a case study, The Deviant Prison brings to light anxieties and other challenges of nineteenth-century prison administration that helped embed our prison system as we know it today. Drawing on organizational theory and providing a rich account of prison life, the institution, and key actors, Ashley T. Rubin examines why Eastern's administrators clung to what was increasingly viewed as an outdated and inhuman model of prison - and what their commitment tells us about penal reform in an era when prisons were still new and carefully scrutinized.

The Deviant Prison

by

ISBN: 9781108754095Publication Date: 2021-01-12Early nineteenth-century American prisons followed one of two dominant models: the Auburn system, in which prisoners performed factory-style labor by day and were placed in solitary confinement at night, and the Pennsylvania system, where prisoners faced 24-hour solitary confinement for the duration of their sentences. By the close of the Civil War, the majority of prisons in the United States had adopted the Auburn system - the only exception was Philadelphia's Eastern State Penitentiary, making it the subject of much criticism and a fascinating outlier. Using the Eastern State Penitentiary as a case study, The Deviant Prison brings to light anxieties and other challenges of nineteenth-century prison administration that helped embed our prison system as we know it today. Drawing on organizational theory and providing a rich account of prison life, the institution, and key actors, Ashley T. Rubin examines why Eastern's administrators clung to what was increasingly viewed as an outdated and inhuman model of prison - and what their commitment tells us about penal reform in an era when prisons were still new and carefully scrutinized. -

The Life of Paper by

ISBN: 0520968824Publication Date: 2017-11-10The Life of Paper offers a wholly original and inspiring analysis of how people facing systematic social dismantling have engaged letter correspondence to remake themselves--from bodily integrity to subjectivity and collective and spiritual being. Exploring the evolution of racism and confinement in California history, this ambitious investigation disrupts common understandings of the early detention of Chinese migrants (1880s-1920s), the internment of Japanese Americans (1930s-1940s), and the mass incarceration of African Americans (1960s-present) in its meditation on modern development and imprisonment as a way of life. Situating letters within global capitalist movements, racial logics, and overlapping modes of social control, Sharon Luk demonstrates how correspondence becomes a poetic act of reinvention and a way to live for those who are incarcerated. -

Surviving Incarceration by

ISBN: 1771120541Publication Date: 2014-05-30This book outlines the modern "inmate code" that governs prisoner behaviours, the formal controls put forth by the administration, the dynamics that shape sex-offender experiences of incarceration, and the personal growth experiences of many prisoners as they cope with incarceration. -

Disability Incarcerated by

ISBN: 1137388471Publication Date: 2014-05-29Disability Incarcerated gathers thirteen contributions from an impressive array of fields. Taken together, these essays assert that a complex understanding of disability is crucial to an understanding of incarceration, and that we must expand what has come to be called 'incarceration.' The chapters in this book examine a host of sites, such as prisons, institutions for people with developmental disabilities, psychiatric hospitals, treatment centers, special education, detention centers, and group homes; explore why various sites should be understood as incarceration; and discuss the causes and effects of these sites historically and currently. This volume includes a preface by Professor Angela Y. Davis and an afterword by Professor Robert McRuer. -

A Plague of Prisons by

ISBN: 9781595589538Publication Date: 2013-05-28The public health expert and prison reform activist offers "meticulous analysis" on our criminal justice system and the plague of American incarceration (The Washington Post). An internationally recognized public health scholar, Ernest Drucker uses the tools of epidemiology to demonstrate that incarceration in the United States has become an epidemic--a plague upon our body politic. He argues that imprisonment, originally conceived as a response to the crimes of individuals, has become "mass incarceration": a destabilizing force that damages the very social structures that prevent crime. Drucker tracks the phenomenon of mass incarceration using basic public health concepts--"incidence and prevalence," "outbreaks," "contagion," "transmission," "potential years of life lost." The resulting analysis demonstrates that our unprecedented rates of incarceration have the contagious and self-perpetuating features of the plagues of previous centuries. Sure to provoke debate and shift the paradigm of how we think about punishment, A Plague of Prisons offers a novel perspective on criminal justice in twenty-first-century America. "How did America's addiction to prisons and mass incarceration get its start and how did it spread from state to state? Of the many attempts to answer this question, none make as much sense as the explanation found in [this] book." --The Philadelphia Inquirer -

Dark Matters by

ISBN: 9780822359197Publication Date: 2015-10-02In Dark Matters Simone Browne locates the conditions of blackness as a key site through which surveillance is practiced, narrated, and resisted. She shows how contemporary surveillance technologies and practices are informed by the long history of racial formation and by the methods of policing black life under slavery, such as branding, runaway slave notices, and lantern laws. Placing surveillance studies into conversation with the archive of transatlantic slavery and its afterlife, Browne draws from black feminist theory, sociology, and cultural studies to analyze texts as diverse as the methods of surveilling blackness she discusses: from the design of the eighteenth-century slave ship Brooks, Jeremy Bentham's Panopticon, and The Book of Negroes, to contemporary art, literature, biometrics, and post-9/11 airport security practices. Surveillance, Browne asserts, is both a discursive and material practice that reifies boundaries, borders, and bodies around racial lines, so much so that the surveillance of blackness has long been, and continues to be, a social and political norm. -

The Law Is a White Dog by

ISBN: 9781400838592Publication Date: 2011-02-07A fascinating account of how the law determines or dismantles identity and personhood Abused dogs, prisoners tortured in Guantánamo and supermax facilities, or slaves killed by the state--all are deprived of personhood through legal acts. Such deprivations have recurred throughout history, and the law sustains these terrors and banishments even as it upholds the civil order. Examining such troubling cases, The Law Is a White Dog tackles key societal questions: How does the law construct our identities? How do its rules and sanctions make or unmake persons? And how do the supposedly rational claims of the law define marginal entities, both natural and supernatural, including ghosts, dogs, slaves, terrorist suspects, and felons? Reading the language, allusions, and symbols of legal discourse, and bridging distinctions between the human and nonhuman, Colin Dayan looks at how the law disfigures individuals and animals, and how slavery, punishment, and torture create unforeseen effects in our daily lives. Moving seamlessly across genres and disciplines, Dayan considers legal practices and spiritual beliefs from medieval England, the North American colonies, and the Caribbean that have survived in our legal discourse, and she explores the civil deaths of felons and slaves through lawful repression. Tracing the legacy of slavery in the United States in the structures of the contemporary American prison system and in the administrative detention of ghostly supermax facilities, she also demonstrates how contemporary jurisprudence regarding cruel and unusual punishment prepared the way for abuses in Abu Ghraib and Guantánamo. Using conventional historical and legal sources to answer unconventional questions, The Law Is a White Dog illuminates stark truths about civil society's ability to marginalize, exclude, and dehumanize. -

Race, Incarceration, and American Values by

ISBN: 0262260948Publication Date: 2008-08-22Why stigmatizing and confining a large segment of our population should be unacceptable to all Americans. The United States, home to five percent of the world's population, now houses twenty-five percent of the world's prison inmates. Our incarceration rate--at 714 per 100,000 residents and rising--is almost forty percent greater than our nearest competitors (the Bahamas, Belarus, and Russia). More pointedly, it is 6.2 times the Canadian rate and 12.3 times the rate in Japan. Economist Glenn Loury argues that this extraordinary mass incarceration is not a response to rising crime rates or a proud success of social policy. Instead, it is the product of a generation-old collective decision to become a more punitive society. He connects this policy to our history of racial oppression, showing that the punitive turn in American politics and culture emerged in the post-civil rights years and has today become the main vehicle for the reproduction of racial hierarchies. Whatever the explanation, Loury argues, the uncontroversial fact is that changes in our criminal justice system since the 1970s have created a nether class of Americans--vastly disproportionately black and brown--with severely restricted rights and life chances. Moreover, conservatives and liberals agree that the growth in our prison population has long passed the point of diminishing returns. Stigmatizing and confining of a large segment of our population should be unacceptable to Americans. Loury's call to action makes all of us now responsible for ensuring that the policy changes. -

From Slave Ship to Supermax by

ISBN: 1439914168Publication Date: 2017-11-30In his cogent and groundbreaking book, From Slave Ship to Supermax, Patrick Elliot Alexander argues that the disciplinary logic and violence of slavery haunt depictions of the contemporary U.S. prison in late twentieth-century Black fiction. Alexander links representations of prison life in James Baldwin's novel If Beale Street Could Talk to his engagements with imprisoned intellectuals like George Jackson, who exposed historical continuities between slavery and mass incarceration. Likewise, Alexander reveals how Toni Morrison's Beloved was informed by Angela Y. Davis's jail writings on slavery-reminiscent practices in contemporary women's facilities. Alexander also examines recurring associations between slave ships and prisons in Charles Johnson's Middle Passage, and connects slavery's logic of racialized premature death to scenes of death row imprisonment in Ernest Gaines' A Lesson Before Dying. Alexander ultimately makes the case that contemporary Black novelists depict racial terror as a centuries-spanning social control practice that structured carceral life on slave ships and slave plantations--and that mass-produces prisoners and prisoner abuse in post-Civil Rights America. These authors expand free society's view of torment confronted and combated in the prison industrial complex, where discriminatory laws and the institutionalization of secrecy have reinstated slavery's system of dehumanization. -

Their Sisters' Keepers by

ISBN: 0472100084Publication Date: 1981-06-15This study of prison reform adds a new chapter to the history of women's struggle for justice in America -

The Rise of the Penitentiary by

ISBN: 0300042973Publication Date: 1992-06-24Before the nineteenth century, American prisons were used to hold people for trial and not to incarcerate them for wrong-doing. Only after independence did American states begin to reject such public punishment as whipping and pillorying and turn to imprisonment instead. In this legal, social, and political history, Adam J. Hirsch explores the reasons behind this change. Hirsch draws on evidence from throughout the early Republic and examines European sources to establish the American penitentiary's ideological origins and parallel development abroad. He focuses on Massachusetts as a case study of the transformation and presents in-depth data from that state. He challenges the notion that the penitentiary came as a by-product of Enlightenment thought, contending instead that the ideological foundations for criminal incarceration had been laid long before the eighteenth century and were premised upon old criminological theories. According to Hirsch, it was not new ideas but new social realities-the increasing urbanization and population mobility that promoted rampant crime-that made the penitentiary attractive to post-revolutionary legislators. Hirsch explores possible economic motives for incarcerating criminals and sentencing them to hard labor, but concludes that there is little evidence to support this. He finds that advocates of the penitentiary intended only that the prison pay for itself through enforced labor. Moreover, prison advocates frequently involved themselves in other contemporary social movements that reflected their concern to promote the welfare of criminals along with other oppressed groups. -

Criminal Intimacy by

ISBN: 0226462269Publication Date: 2008-09-01Sex is usually assumed to be a closely guarded secret of prison life. But it has long been the subject of intense scrutiny by both prison administrators and reformers--as well as a source of fascination and anxiety for the American public. Historically, sex behind bars has evoked radically different responses from professionals and the public alike. In Criminal Intimacy, Regina Kunzel tracks these varying interpretations and reveals their foundational influence on modern thinking about sexuality and identity. Historians have held the fusion of sexual desire and identity to be the defining marker of sexual modernity, but sex behind bars, often involving otherwise heterosexual prisoners, calls those assumptions into question. By exploring the sexual lives of prisoners and the sexual culture of prisons over the past two centuries--along with the impact of a range of issues, including race, class, and gender; sexual violence; prisoners' rights activism; and the HIV epidemic--Kunzel discovers a world whose surprising plurality and mutability reveals the fissures and fault lines beneath modern sexuality itself. Drawing on a wide range of sources, including physicians, psychiatrists, sociologists, correctional administrators, journalists, and prisoners themselves--as well as depictions of prison life in popular culture--Kunzel argues for the importance of the prison to the history of sexuality and for the centrality of ideas about sex and sexuality to the modern prison. In the process, she deepens and complicates our understanding of sexuality in America. -

Buried Lives by

ISBN: 0820341193Publication Date: 2012-03-01Buried Lives offers the first critical examination of the experience of imprisonment in early America. These interdisciplinary essays investigate several carceral institutions to show how confinement shaped identity, politics, and the social imaginary both in the colonies and in the new nation. The historians and literary scholars included in this volume offer a complement and corrective to conventional understandings of incarceration that privilege the intentions of those in power over the experiences of prisoners. Considering such varied settings as jails, penitentiaries, almshouses, workhouses, floating prison ships, and plantations, the contributors reconstruct the struggles of people imprisoned in locations from Antigua to Boston. The essays draw upon a rich array of archival sources from the seventeenth century to the eve of the Civil War, including warden logs, petitions, execution sermons, physicians' clinical notes, private letters, newspaper articles, runaway slave advertisements, and legal documents. Through the voices, bodies, and texts of the incarcerated, Buried Lives reveals the largely ignored experiences of inmates who contested their subjection to regimes of power. -

Liberty's Prisoners by

ISBN: 9780812247572Publication Date: 2015-10-29Liberty's Prisoners examines how changing attitudes about work, freedom, property, and family shaped the creation of the penitentiary system in the United States. The first penitentiary was founded in Philadelphia in 1790, a period of great optimism and turmoil in the Revolution's wake. Those who were previously dependents with no legal standing--women, enslaved people, and indentured servants--increasingly claimed their own right to life, liberty, and happiness. A diverse cast of women and men, including immigrants, African Americans, and the Irish and Anglo-American poor, struggled to make a living. Vagrancy laws were used to crack down on those who visibly challenged longstanding social hierarchies while criminal convictions carried severe sentences for even the most trivial property crimes. The penitentiary was designed to reestablish order, both behind its walls and in society at large, but the promise of reformative incarceration failed from its earliest years. Within this system, women served a vital function, and Liberty's Prisoners is the first book to bring to life the e xperience of African American, immigrant, and poor white women imprisoned in early America. Always a minority of prisoners, women provided domestic labor within the institution and served as model inmates, more likely to submit to the authority of guards, inspectors, and reformers. White men, the primary targets of reformative incarceration, challenged authorities at every turn while African American men were increasingly segregated and denied access to reform. Liberty's Prisoners chronicles how the penitentiary, though initially designed as an alternative to corporal punishment for the most egregious of offenders, quickly became a repository for those who attempted to lay claim to the new nation's promise of liberty. -

The Crisis of Imprisonment by

ISBN: 0511394713Publication Date: 2008-01-01ntroduction: The grounds of legal punishment -- Strains of servitude : legal punishment in the early republic -- Due convictions : contractual penal servitude and its discontents, 1818-1865 -- Commerce upon the throne : the business of imprisonment in Gilded Age America -- Disciplining the state, civilizing the market : the campaign to abolish contract prison labor -- A model servitude : prison reform in the early Progressive Era -- Uses of the state : the dialectics of penal reform in early progressive New York -- American Bastille : Sing Sing and the political crisis of imprisonment -- Changing the subject : the metamorphosis of prison reform in the high Progressive Era -- Laboratory of social justice : the new penologists at Sing Sing, 1915-1917 -- Punishment without labor : towards the modern penal state -- Conclusion: On the crises of imprisonment. -

Laboratories of Virtue by

ISBN: 0807838276Publication Date: 2012-12-01Michael Meranze uses Philadelphia as a case study to analyze the relationship between penal reform and liberalism in early America. In Laboratories of Virtue, he interprets the evolving system of criminal punishment as a microcosm of social tensions that characterized the early American republic. Engaging recent work on the history of punishment in England and continental Europe, Meranze traces criminal punishment from the late colonial system of publicly inflicted corporal penalties to the establishment of penitentiaries in the Jacksonian period. Throughout, he reveals a world of class difference and contested values in which those who did not fit the emerging bourgeois ethos were disciplined and eventually segregated. By focusing attention on the system of public penal labor that developed in the 1780s, Meranze effectively links penal reform to the development of republican principles in the Revolutionary era. His study, richly informed by Foucaultian and Freudian theory, departs from recent scholarship that treats penal reform as a nostalgic effort to reestablish social stability. Instead, Meranze interprets the reform of punishment as a forward-looking project. He argues that the new disciplinary practices arose from the reformers' struggle to contain or eliminate contradictions to their vision of an enlightened, liberal republic. -

Slavery by Another Name by

ISBN: 0385506252Publication Date: 2008-03-25In this groundbreaking book, Blackmon brings to light one of the most shameful chapters in American history--the re-enslavement of black Americans from the Civil War to World War II--in a moving, sobering account that explores the insidious legacy of white racism that reverberates today. -

Black Prisoners and Their World by

ISBN: 0813919819Publication Date: 2000-10-29In the late nineteenth century, prisoners in Alabama, the vast majority of them African Americans, were forced to work as coal miners under the most horrendous conditions imaginable. Black Prisoners and Their World draws on a variety of sources, including the reports and correspondence of prison inspectors and letters from prisoners and their families, to explore the history of the African American men and women whose labor made Alabama's prison system the most profitable in the nation. To coal companies and the state of Alabama, black prisoners provided, respectively, sources of cheap labor and state revenue. By 1883, a significant percentage of the workforce in the Birmingham coal industry was made up of convicts. But to the families and communities from which the prisoners came, the convict lease was a living symbol of the dashed hopes of Reconstruction. Indeed, the lease--the system under which the prisoners labored for the profit of the company and the state--demonstrated Alabama's reluctance to let go of slavery and its determination to pursue profitable prisons no matter what the human cost. Despite the efforts of prison officials, progressive reformers, and labor unions, the state refused to take prisoners out of the coal mines. In the course of her narrative, Mary Ellen Curtin describes how some prisoners died while others endured unspeakable conditions and survived. Curtin argues that black prisoners used their mining skills to influence prison policy, demand better treatment, and become wage-earning coal miners upon their release. Black Prisoners and Their World unearths new evidence about life under the most repressive institution in the New South. Curtin suggests disturbing parallels between the lease and today's burgeoning system of private incarceration. -

Chained in Silence by

ISBN: 1469622475Publication Date: 2015-04-27In 1868, the state of Georgia began to make its rapidly growing population of prisoners available for hire. The resulting convict leasing system ensnared not only men but also African American women, who were forced to labor in camps and factories to make profits for private investors. In this vivid work of history, Talitha L. LeFlouria draws from a rich array of primary sources to piece together the stories of these women, recounting what they endured in Georgia's prison system and what their labor accomplished. LeFlouria argues that African American women's presence within the convict lease and chain-gang systems of Georgia helped to modernize the South by creating a new and dynamic set of skills for black women. At the same time, female inmates struggled to resist physical and sexual exploitation and to preserve their human dignity within a hostile climate of terror. This revealing history redefines the social context of black women's lives and labor in the New South and allows their stories to be told for the first time. -

Twice the Work of Free Labor by

ISBN: 1859849911Publication Date: 1996-01-17This volume is both a study of penal labour in the Southern United States and a revisionist analysis of the political economy of the South after the Civil War. -

No Mercy Here by

ISBN: 9781469627601Publication Date: 2016-02-17In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries imprisoned black women faced wrenching forms of gendered racial terror and heinous structures of economic exploitation. Subjugated as convict laborers and forced to serve additional time as domestic workers before they were allowed their freedom, black women faced a pitiless system of violence, terror, and debasement. Drawing upon black feminist criticism and a diverse array of archival materials, Sarah Haley uncovers imprisoned women's brutalization in local, county, and state convict labor systems, while also illuminating the prisoners' acts of resistance and sabotage, challenging ideologies of racial capitalism and patriarchy and offering alternative conceptions of social and political life. A landmark history of black women's imprisonment in the South, this book recovers stories of the captivity and punishment of black women to demonstrate how the system of incarceration was crucial to organizing the logics of gender and race, and constructing Jim Crow modernity. -

One Dies, Get Another by

ISBN: 9781643364100Publication Date: 1996He describes the prisoners' daily existence, profiles the individuals who leased convicts, and reveals both the inhumanity of the leasing laws and the centrality of race relations in the establishment and perpetuation of convict leasing. In considering the longevity of the practice, Mancini takes issue with the widespread notion that convict leasing was an aberration in a generally progressive history of criminal justice. In explaining its dramatic demise, Mancini contends that moral opposition was a distinctly minor force in the abolition of the practice and that only a combination of rising lease prices and years of economic decline forced an end to convict leasing in the South.

In his seminal study of convict leasing in the post-Civil War South, Matthew J. Mancini chronicles one of the harshest, most exploitative labor systems in American history. Devastated by war, bewildered by peace, and unprepared to confront the problems of prison management, Southern states sought to alleviate the need for cheap labor, a perceived rise in criminal behavior, and the bankruptcy of their state treasuries. Mancini describes the policy of leasing prisoners to individuals and corporations as one that, in addition to reducing prison populations and generating revenues, offered a means of racial subordination and labor discipline. He identifies commonalities that, despite the seemingly uneven enforcement of convict leasing across state lines, bound the South together for more than half a century in reliance on an institution of almost unrelieved brutality. -

Worse Than Slavery by

ISBN: 0684830957Publication Date: 1997-04-22In this sensitively told tale of suffering, brutality, and inhumanity, Worse Than Slavery is an epic history of race and punishment in the deepest South from emancipation to the Civil Rights Era--and beyond. Immortalized in blues songs and movies like Cool Hand Luke and The Defiant Ones, Mississippi's infamous Parchman State Penitentiary was, in the pre-civil rights south, synonymous with cruelty. Now, noted historian David Oshinsky gives us the true story of the notorious prison, drawing on police records, prison documents, folklore, blues songs, and oral history, from the days of cotton-field chain gangs to the 1960s, when Parchman was used to break the wills of civil rights workers who journeyed south on Freedom Rides.