Ethnographic Cinema: an Introduction

Ethnographic cinema is as old as cinema itself. It is a porous genre that typically refers to films made in the context of fieldwork-based anthropological research, but which frequently crosses the boundaries between anthropology, sociology, documentary film, art cinema, and related disciplines.

Below, you will find an introduction to the history and development of ethnographic cinema. The guide focuses on key films and filmmakers that have shaped the field, approaching filmmaking not as a means of illustrating arguments made elsewhere in text, but as a mode of inquiry in its own right.

Navigate the sidebar menu to find films organized by geographic region. Please note that this guide is meant to highlight select films from Emory's extensive collection and is not at all exhaustive.

Note: Some streaming titles can only be licensed for three or five years at a time. Check with the anthropology subject librarian to ensure the title is still available when needed for your course.

Foundations: Early Ethnographic Films

Cinema's value for anthropological research was clear almost immediately. In 1898, only a few years after the Lumière brothers first projected a motion picture for a public audience, A.C. Haddon made a series of films while conducting ethnographic fieldwork as part of the Cambridge Expedition to the Torres Straits. In 1922, Robert Flaherty's widely popular Nanook of the North broke new ground, demonstrating that it was possible to craft a compelling feature-length film from elements of reality, leading to the emergence of a new genre: "documentary film."

Beginning with Haddon and extending into the films by Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson, this early period of ethnographic cinema tended to focus on performance—using film to elicit demonstrations of ritual, dance, hunting and cooking technique, and so on, with the camera standing in for an audience.

-

Torres Strait Islanders

by

Publication Date: 1898Torres Strait Islanders contains the surviving four-and-a-half minutes of footage shot by A.C. Haddon during an expedition conducted by Cambridge University to Murray Island in the Torres Straits, in 1898. Composed of five short sequences, this film is the world’s first field footage of indigenous peoples in Australia. Made three years after the invention of the cine-camera, Torres Strait Islander men perform traditional dance sequences of the Malu-Bomai Ceremony and demonstrate a fire-making technique. In the final film, a small group of young mainland Aboriginal men who have traveled over to Murray Island demonstrate the shake-a-leg dance on the beach.

Torres Strait Islanders

by

Publication Date: 1898Torres Strait Islanders contains the surviving four-and-a-half minutes of footage shot by A.C. Haddon during an expedition conducted by Cambridge University to Murray Island in the Torres Straits, in 1898. Composed of five short sequences, this film is the world’s first field footage of indigenous peoples in Australia. Made three years after the invention of the cine-camera, Torres Strait Islander men perform traditional dance sequences of the Malu-Bomai Ceremony and demonstrate a fire-making technique. In the final film, a small group of young mainland Aboriginal men who have traveled over to Murray Island demonstrate the shake-a-leg dance on the beach. -

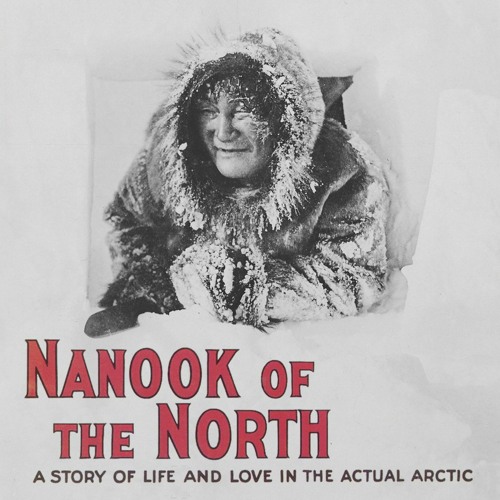

Nanook of the North

by

Publication Date: 1922Robert Flaherty's classic film tells the story of Eskimo (Inuit) hunter Nanook and his family as they struggle to survive in the harsh conditions of Canada's Hudson Bay region. The title role of Nanook was played by Allakariallak, a celebrated hunter of the Itivimuit tribe, with whom Flaherty collaborated to carefully plan scenes that would demonstrate traditional ways of hunting, building igloos, and other life practices that were disappearing from the region.

Nanook of the North

by

Publication Date: 1922Robert Flaherty's classic film tells the story of Eskimo (Inuit) hunter Nanook and his family as they struggle to survive in the harsh conditions of Canada's Hudson Bay region. The title role of Nanook was played by Allakariallak, a celebrated hunter of the Itivimuit tribe, with whom Flaherty collaborated to carefully plan scenes that would demonstrate traditional ways of hunting, building igloos, and other life practices that were disappearing from the region. -

Trance and Dance in Bali

by

Publication Date: 1951A performance of the kris dance, a Balinese ceremonial dance which dramatizes the never-ending struggle between the witch and the dragon—the death-dealing and the life-protecting—as it is given in the village of Pagoetan in 1937-1939. Dancers go into violent trance seizures and turn their krisses (daggers) against their breasts without injury. Consciousness is restored with incense and holy water. Balinese gamelan music forms the soundtrack, along with Margaret Mead's narration.

Trance and Dance in Bali

by

Publication Date: 1951A performance of the kris dance, a Balinese ceremonial dance which dramatizes the never-ending struggle between the witch and the dragon—the death-dealing and the life-protecting—as it is given in the village of Pagoetan in 1937-1939. Dancers go into violent trance seizures and turn their krisses (daggers) against their breasts without injury. Consciousness is restored with incense and holy water. Balinese gamelan music forms the soundtrack, along with Margaret Mead's narration.

Ethnographic Film: Science or Art?

What is ethnographic cinema: art or science? What is its purpose: research, teaching, analysis, interpretation, communicating with the public, or something else entirely? In the second half of the twentieth century, debates about the epistemological value of ethnographic cinema periodically gripped the field, especially as few anthropologists had any training in how to understand and critically evaluate films. Timothy Asch and John Marshall both experimented with approaches to filmmaking for the purpose of anthropological analysis and teaching. Robert Gardner, who had worked on Marshall's first film The Hunters, took a different approach, experimenting with using the expressive capacities of cinema to explore the universal significance of particular stories.

-

The !Kung Series

by

Over the course of his career, filmmaker John Marshall shot more than one million feet of film and video (722 hours) of the Ju/'hoansi (!Kung Bushmen) of Namibia's Kalahari Desert. This body of work is unrivalled as a long-term visual study of a single group of people. Contained in Marshall's footage are the personal histories of individuals, documents of a now non-existent way of life, and the unfolding of massive social and economic change as experienced by one group of people over a period of fifty years. Marshall's approach to filmmaking evolved alongside changes in film and video technology, in the fields of anthropology and ethnographic and documentary film, and on a very personal level, in Marshall's relationship to the Ju/'hoansi.

The !Kung Series

by

Over the course of his career, filmmaker John Marshall shot more than one million feet of film and video (722 hours) of the Ju/'hoansi (!Kung Bushmen) of Namibia's Kalahari Desert. This body of work is unrivalled as a long-term visual study of a single group of people. Contained in Marshall's footage are the personal histories of individuals, documents of a now non-existent way of life, and the unfolding of massive social and economic change as experienced by one group of people over a period of fifty years. Marshall's approach to filmmaking evolved alongside changes in film and video technology, in the fields of anthropology and ethnographic and documentary film, and on a very personal level, in Marshall's relationship to the Ju/'hoansi. -

The Ax Fight

by

Publication Date: 1975A fight broke out in Mishimishimabowei-teri on the second day of Napoleon Chagnon and Tim Asch's stay in the village in 1971. The event lasted about half an hour, ten minutes of which were filmed. The film is constructed of four parts. The first consists of an unedited version of what the cameraman saw and the sound technician recorded, including the filmmakers' comments. The following three parts attempt to resolve the apparent chaos of the first part into anthropological explanation and analysis. The Ax Fight thus operates on several levels. It plunges the viewer into the anthropology of Yanomamö kinship, alliance, and village fission; of violence and conflict resolution. At the same time it raises questions about how anthropologists and filmmakers make sense of and translate their experience into meaningful words and coherent, moving images.

The Ax Fight

by

Publication Date: 1975A fight broke out in Mishimishimabowei-teri on the second day of Napoleon Chagnon and Tim Asch's stay in the village in 1971. The event lasted about half an hour, ten minutes of which were filmed. The film is constructed of four parts. The first consists of an unedited version of what the cameraman saw and the sound technician recorded, including the filmmakers' comments. The following three parts attempt to resolve the apparent chaos of the first part into anthropological explanation and analysis. The Ax Fight thus operates on several levels. It plunges the viewer into the anthropology of Yanomamö kinship, alliance, and village fission; of violence and conflict resolution. At the same time it raises questions about how anthropologists and filmmakers make sense of and translate their experience into meaningful words and coherent, moving images. -

Dead Birds

by

Publication Date: 1964Robert Gardner's seminal 1964 film Dead Birds is a portrait of the lives, beliefs, practices and ritual warfare of the Hubula people of the remote Baliem Valley in western New Guinea, now part of Indonesia. The film focuses on Weyak, the farmer and warrior, and on Pua, the young swineherd, following them through the events of Dani life: sweet potato horticulture, pig keeping, salt winning, battles, raids and ceremonies. Gardner: "Dead Birds has a meaning which is both immediate and allegorical. In the Dani language it refers to the weapons and ornaments recovered in battle. Its other more poetic meaning comes from the Dani belief that people, because they are like birds, must die."

Dead Birds

by

Publication Date: 1964Robert Gardner's seminal 1964 film Dead Birds is a portrait of the lives, beliefs, practices and ritual warfare of the Hubula people of the remote Baliem Valley in western New Guinea, now part of Indonesia. The film focuses on Weyak, the farmer and warrior, and on Pua, the young swineherd, following them through the events of Dani life: sweet potato horticulture, pig keeping, salt winning, battles, raids and ceremonies. Gardner: "Dead Birds has a meaning which is both immediate and allegorical. In the Dani language it refers to the weapons and ornaments recovered in battle. Its other more poetic meaning comes from the Dani belief that people, because they are like birds, must die." -

Forest of Bliss

by

Publication Date: 1986Forest of Bliss is an unsparing yet redemptive account of the inevitable griefs, religious passions and frequent happinesses that punctuate daily life in Benares (now Varanasi), India's most holy city. The film unfolds from one sunrise to the next without commentary, subtitles or dialogue. It is an attempt to give the viewer a wholly authentic, though greatly magnified and concentrated, sense of participation in the experiences examined by the film.

Forest of Bliss

by

Publication Date: 1986Forest of Bliss is an unsparing yet redemptive account of the inevitable griefs, religious passions and frequent happinesses that punctuate daily life in Benares (now Varanasi), India's most holy city. The film unfolds from one sunrise to the next without commentary, subtitles or dialogue. It is an attempt to give the viewer a wholly authentic, though greatly magnified and concentrated, sense of participation in the experiences examined by the film.

New Directions: Observational Cinema and Cinéma vérité

Beginning in the late 1950s, innovations in film technology—especially synchronized sound and lighter, more mobile cameras—made possible new directions for ethnographic cinema. New "schools" of filmmaking developed, with David MacDougall and Jean Rouch as leading figures of Observational Cinema and Cinéma vérité, respectively. Partly as a reaction against heavily narrated, overly didactic films, MacDougall and Rouch both experimented with ways of placing the camera into the flow of everyday life and collaborating with their film subjects—with an impressive breadth of results. Their films suggested new approaches to the anthropological project, anticipating later inquiries into the relationship between knowing and seeing, the formal and aesthetic qualities of ethnography, and the ethics of collaboration.

-

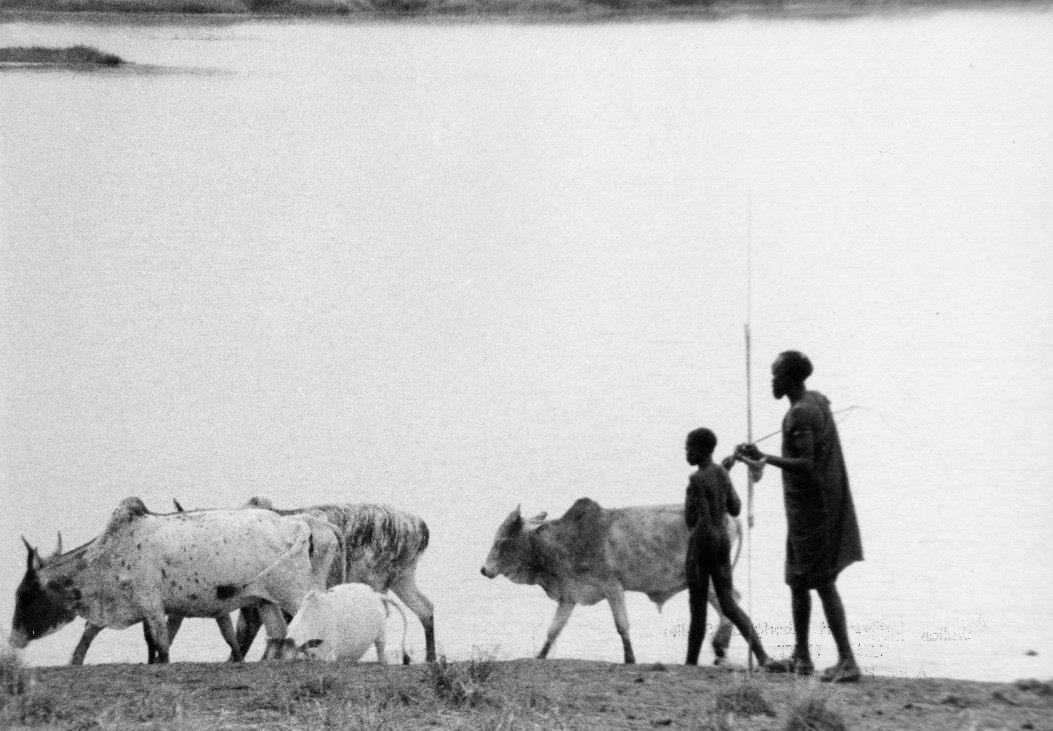

To Live With Herds

by

Publication Date: 1974This classic, widely acclaimed film on the Jie of Uganda, produced by the renowned ethnographic filmmaking team of David and Judith MacDougall, examines the effects of nation building in pre-Amin Uganda on the seminomadic, pastoral Jie. Much more than an intrinsically interesting historical document, it has achieved classic status among ethnographic films owing to its remarkable success in developing a coherent analytical statement about its subjects' situation, yet at the same time allowing them to speak for themselves about the world as they see and experience it.The film explores life in a traditional Jie homestead during a harsh dry season. The talk and work of adults go on, but there is also hardship and worry, exacerbated by government policies that seem to attack rather than support the values and economic base of Jie society.A mother counts her children; among them is a son she hardly knows who has joined the educated bureaucracy. Later we find him supervising famine relief for his own people in a situation that seems far beyond his control.At the end of the film Logoth, the protector of the homestead, travels to the west to rejoin his herds in an area of relative plenty; at least for the time being his life seems free from official interference.

To Live With Herds

by

Publication Date: 1974This classic, widely acclaimed film on the Jie of Uganda, produced by the renowned ethnographic filmmaking team of David and Judith MacDougall, examines the effects of nation building in pre-Amin Uganda on the seminomadic, pastoral Jie. Much more than an intrinsically interesting historical document, it has achieved classic status among ethnographic films owing to its remarkable success in developing a coherent analytical statement about its subjects' situation, yet at the same time allowing them to speak for themselves about the world as they see and experience it.The film explores life in a traditional Jie homestead during a harsh dry season. The talk and work of adults go on, but there is also hardship and worry, exacerbated by government policies that seem to attack rather than support the values and economic base of Jie society.A mother counts her children; among them is a son she hardly knows who has joined the educated bureaucracy. Later we find him supervising famine relief for his own people in a situation that seems far beyond his control.At the end of the film Logoth, the protector of the homestead, travels to the west to rejoin his herds in an area of relative plenty; at least for the time being his life seems free from official interference. -

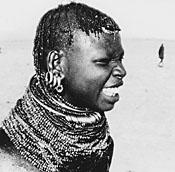

Turkana Conversations Trilogy

by

Publication Date: 1980This classic trilogy of films by David and Judith MacDougall focuses on the Turkana people of Kenya. "Lorang's Way" (1977) is a multifaceted portrait of Lorang, the head of the homestead and one of the important senior men of the Turkana. Because they are relatively isolated and self-sufficient, most Turkana (including Lorang’s son) see their way of life continuing unchanged into the future. But Lorang thinks otherwise, for he has seen something of the outside world. In "The Wedding Camels," (1980) one of Lorang’s daughters, Akai, is going to marry one of his friends and age-mates, Kongu. Because of the close ties between the two men everything should go smoothly, but the pressures within the two families are such that the wedding negotiations over the bridewealth become increasingly tense. "A Wife Among Wives" (1981) investigates the views of the Turkana, and especially Turkana women, on marriage and polygyny. As the plans for a marriage in a nearby homestead unfold, the film explores why a Turkana woman would want her husband to take a second (or third) wife, and how the system of polygyny can be a source of solidarity among women while at the same time it may brutally disregard individual feelings.

Turkana Conversations Trilogy

by

Publication Date: 1980This classic trilogy of films by David and Judith MacDougall focuses on the Turkana people of Kenya. "Lorang's Way" (1977) is a multifaceted portrait of Lorang, the head of the homestead and one of the important senior men of the Turkana. Because they are relatively isolated and self-sufficient, most Turkana (including Lorang’s son) see their way of life continuing unchanged into the future. But Lorang thinks otherwise, for he has seen something of the outside world. In "The Wedding Camels," (1980) one of Lorang’s daughters, Akai, is going to marry one of his friends and age-mates, Kongu. Because of the close ties between the two men everything should go smoothly, but the pressures within the two families are such that the wedding negotiations over the bridewealth become increasingly tense. "A Wife Among Wives" (1981) investigates the views of the Turkana, and especially Turkana women, on marriage and polygyny. As the plans for a marriage in a nearby homestead unfold, the film explores why a Turkana woman would want her husband to take a second (or third) wife, and how the system of polygyny can be a source of solidarity among women while at the same time it may brutally disregard individual feelings. -

Jaguar

by

Publication Date: 1967One of Jean Rouch's classic ethnofictions, the film follows three young Songhay men from Niger -- Lam Ibrahim, Illo Goudel'ize, and the legendary performer Damouré Zika -- on a journey to the Gold Coast (modern day Ghana). Drawing from his own fieldwork on intra-African migration, the results of which he published in the 1956 book Migrations au Ghana, Rouch collaborated with his three subjects on an improvisational narrative. The four filmed the trip in mid-1950s, and reunited a few years later to record the sound, the participants remembering dialogue and making up commentary. The result is a playful film that finds three African men performing an ethnography of their own culture.

Jaguar

by

Publication Date: 1967One of Jean Rouch's classic ethnofictions, the film follows three young Songhay men from Niger -- Lam Ibrahim, Illo Goudel'ize, and the legendary performer Damouré Zika -- on a journey to the Gold Coast (modern day Ghana). Drawing from his own fieldwork on intra-African migration, the results of which he published in the 1956 book Migrations au Ghana, Rouch collaborated with his three subjects on an improvisational narrative. The four filmed the trip in mid-1950s, and reunited a few years later to record the sound, the participants remembering dialogue and making up commentary. The result is a playful film that finds three African men performing an ethnography of their own culture. -

Les Maitres fous (The Mad Masters)

by

Publication Date: 1955The Mad Masers (Les Maitres fous), the controversial but widely celebrated work by ethnographic filmmaker Jean Rouch, depicts the annual ceremony of the Hauku cult, a social and religious movement which was widespread in French colonial Africa from the 1920s to the 1950s. Participants in the ceremony mimic the elaborate military ceremonies of their colonial occupiers. Rouch does not document this from a distance, but, using a hand-held camera and quick cuts, creates an effect he called "cine-trance".

Les Maitres fous (The Mad Masters)

by

Publication Date: 1955The Mad Masers (Les Maitres fous), the controversial but widely celebrated work by ethnographic filmmaker Jean Rouch, depicts the annual ceremony of the Hauku cult, a social and religious movement which was widespread in French colonial Africa from the 1920s to the 1950s. Participants in the ceremony mimic the elaborate military ceremonies of their colonial occupiers. Rouch does not document this from a distance, but, using a hand-held camera and quick cuts, creates an effect he called "cine-trance". -

Chronique d'un été (Chronicle of a Summer)

by

Publication Date: 1960The fascinating result of a collaboration between filmmaker-anthropologist Jean Rouch and sociologist Edgar Morin, this vanguard work of what Morin termed cinéma- vérité is a brilliantly conceived and realized sociopolitical diagnosis of the early sixties in France. Simply by interviewing a group of Paris residents in the summer of 1960—beginning with the provocative and eternal question “Are you happy?” and expanding to political issues, including the ongoing Algerian War—Rouch and Morin reveal the hopes and dreams of a wide array of people, from artists to factory workers, from an Italian émigré to an African student.

Chronique d'un été (Chronicle of a Summer)

by

Publication Date: 1960The fascinating result of a collaboration between filmmaker-anthropologist Jean Rouch and sociologist Edgar Morin, this vanguard work of what Morin termed cinéma- vérité is a brilliantly conceived and realized sociopolitical diagnosis of the early sixties in France. Simply by interviewing a group of Paris residents in the summer of 1960—beginning with the provocative and eternal question “Are you happy?” and expanding to political issues, including the ongoing Algerian War—Rouch and Morin reveal the hopes and dreams of a wide array of people, from artists to factory workers, from an Italian émigré to an African student.

21st-Century Experiments in Ethnographic Cinema

In the twenty-first century, ethnographic filmmakers continue experimenting with cinematic techniques, technologies, and avenues of distribution to discover new ways of making anthropology on film, while drawing on past models. Lucien Taylor, Véréna Paravel, and J.D. Sniadecki of Harvard's Sensory Ethnographic Lab incorporate a variety of cameras and cinematographic techniques in a synthetic approach that recalls the films of Robert Gardner. Nicola Mai references Jean Rouch's 'ethnofictions' as influential in his approach to making collaborative films that are projected in theaters and art galleries alike. Anna Grimshaw of Emory University's Visual Scholarship Initiative extends the theory and techniques of observational cinema into an exploration of the possibilities afforded to anthropology by multi-part film series.

-

Leviathan

by

In this cinema verité work set entirely on a groundfish trawler out of New Bedford, Mass., the filmmakers have avoided the standard equipment of interviews, analysis and explanation. A product of the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard, the film offers not information but immersion in wind, water, grinding machinery and piscine agony. The brutality of fishing, as opposed to its romance, is emphasized here. The experience is often unnerving and sometimes nauseating, because of the motions of the juddering, swaying hand-held camera and also because of the distended eyes, gasping mouths and mutilated flesh of the catch. Presented without dialogue, speech is drowned out by the roar of the elements and the screech and thump of engines and hydraulic winches.

Leviathan

by

In this cinema verité work set entirely on a groundfish trawler out of New Bedford, Mass., the filmmakers have avoided the standard equipment of interviews, analysis and explanation. A product of the Sensory Ethnography Lab at Harvard, the film offers not information but immersion in wind, water, grinding machinery and piscine agony. The brutality of fishing, as opposed to its romance, is emphasized here. The experience is often unnerving and sometimes nauseating, because of the motions of the juddering, swaying hand-held camera and also because of the distended eyes, gasping mouths and mutilated flesh of the catch. Presented without dialogue, speech is drowned out by the roar of the elements and the screech and thump of engines and hydraulic winches. -

El Mar La Mar

by

Publication Date: 2017El Mar La Mar weaves together harrowing oral histories of the Mexican-American border region with hand-processed, 16mm images of the flora, fauna, and items left behind by those who've made the hazardous trek. Over a black screen, subjects speak of their intense, mythic experiences in the desert: A man tells of a fifteen-foot-tall monster said to haunt the region, while a border patrolman spins a similarly bizarre tale of man versus beast. A sonically rich soundtrack adds to the eerie atmosphere as the call of birds and other nocturnal noises invisibly populate the austere landscape. Emerging from the ethos of Harvard's Sensory Ethnography Lab, Sniadecki's attentive documentary approach mixes perfectly with Bonnetta's meditations on the materiality of film. Through their stunning collaboration, they create a mystical, folktale-like atmosphere dense with memories, ghosts and the remains of desire.

El Mar La Mar

by

Publication Date: 2017El Mar La Mar weaves together harrowing oral histories of the Mexican-American border region with hand-processed, 16mm images of the flora, fauna, and items left behind by those who've made the hazardous trek. Over a black screen, subjects speak of their intense, mythic experiences in the desert: A man tells of a fifteen-foot-tall monster said to haunt the region, while a border patrolman spins a similarly bizarre tale of man versus beast. A sonically rich soundtrack adds to the eerie atmosphere as the call of birds and other nocturnal noises invisibly populate the austere landscape. Emerging from the ethos of Harvard's Sensory Ethnography Lab, Sniadecki's attentive documentary approach mixes perfectly with Bonnetta's meditations on the materiality of film. Through their stunning collaboration, they create a mystical, folktale-like atmosphere dense with memories, ghosts and the remains of desire. -

Travel

by

Publication Date: 2016Joy left Nigeria to help her family after her father's death. She knew that she was going to sell sex in France, but she was unaware of the degree of exploitation that she would face. With the help of an association she obtains asylum, but to help her family and live her life, she continues selling sex. This two-screen film installation and documentary ethnofiction was co-written by Nicola Mai and eight Nigerian women with experiences of migration, sex work and trafficking. Joy is one of several fictional characters embodying their individual and collective experiences. In order to protect their identities these roles are played by non-professional actresses including some of the film's co-authors.

Travel

by

Publication Date: 2016Joy left Nigeria to help her family after her father's death. She knew that she was going to sell sex in France, but she was unaware of the degree of exploitation that she would face. With the help of an association she obtains asylum, but to help her family and live her life, she continues selling sex. This two-screen film installation and documentary ethnofiction was co-written by Nicola Mai and eight Nigerian women with experiences of migration, sex work and trafficking. Joy is one of several fictional characters embodying their individual and collective experiences. In order to protect their identities these roles are played by non-professional actresses including some of the film's co-authors. -

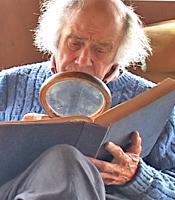

Mr. Coperthwaite: A Life in the Maine Woods

by

Publication Date: 2014In 1960, Bill Coperthwaite bought 300 acres of forest wilderness in Machiasport, Maine. Influenced by the poetry of Emily Dickinson and by the back-to-the-land movement of Scott and Helen Nearing, he was committed to crafting what he called “a handmade life.” For more than 50 years until his death in 2013, Bill Coperthwaite lived and worked in the forest. He was a builder of yurts, and a maker of spoons, bowls, and chairs. The four films chart Coperthwaite’s life as it unfolds over the course of a year. They explore the changing character of work through the seasons and the distinctive temporality of specific tasks. "Spring in Dickinson’s Reach" is the longest film and the starting point of the series. It establishes, literally and metaphorically, the scope of Bill Coperthwaite’s world. In contrast, "A Summer Task" is tightly focused and follows a single activity in painstaking detail. "Autumn’s Work" records the passage of time through a change in the seasons as Bill makes preparations for winter. "Winter Days" draws the viewer into the quiet space and routine of the year’s end. Who is Bill Coperthwaite? How do we understand his life? What does it mean to dwell in nature?

Mr. Coperthwaite: A Life in the Maine Woods

by

Publication Date: 2014In 1960, Bill Coperthwaite bought 300 acres of forest wilderness in Machiasport, Maine. Influenced by the poetry of Emily Dickinson and by the back-to-the-land movement of Scott and Helen Nearing, he was committed to crafting what he called “a handmade life.” For more than 50 years until his death in 2013, Bill Coperthwaite lived and worked in the forest. He was a builder of yurts, and a maker of spoons, bowls, and chairs. The four films chart Coperthwaite’s life as it unfolds over the course of a year. They explore the changing character of work through the seasons and the distinctive temporality of specific tasks. "Spring in Dickinson’s Reach" is the longest film and the starting point of the series. It establishes, literally and metaphorically, the scope of Bill Coperthwaite’s world. In contrast, "A Summer Task" is tightly focused and follows a single activity in painstaking detail. "Autumn’s Work" records the passage of time through a change in the seasons as Bill makes preparations for winter. "Winter Days" draws the viewer into the quiet space and routine of the year’s end. Who is Bill Coperthwaite? How do we understand his life? What does it mean to dwell in nature?

Indigenous Critique

The concept of a genre of "indigenous film" remains somewhat contested. It is often glossed as the historical emergence of the former subjects of ethnographic cinema taking up the camera for themselves. Yet, this occurred in uneven ways, following distinct trajectories particular to their political context. At the heart of the problem is how broadly to apply it: should it be limited to those filmmakers who self-consciously position their work in the terms of indigenous, Aboriginal, or First Nations politics, or does it also include the emergence of Third World national cinemas following anti-colonial struggles in Africa, Asia, and Latin America?

Rather than parse out categories from the outset, we opted for a more inclusive approach, allowing the individual films to exhibit their particular perspective and context. A guiding principle was that "indigenous" is a political concept, not merely a descriptive category. We focused on filmmakers who approached filmmaking as a mode of self-determination. We also chose to highlight films recorded in the filmmaker's native languages--sometimes for the first time.

Finally, this section highlights films that can be viewed productively in a critical relationship with other films included in this guide. Consider, for example, pairing Robert Flaherty's Nanook of the North (1922) with Zacharias Kunuk's Atanarjuat, The Fast Runner (2001). Or Jean Rouch's films with those by Ousmane Sembene or Safi Faye, who played a role in one of Rouch's films before traveling from Senegal to France to study anthropology herself.

-

Video in the Villages

Publication Date: 1987-2004Since the 1980s, the Video in the Villages' project has encouraged the encounter of the Amazonian Indians with their images. The project's proposal is to turn video into a tool that will enable the expression of their identity, reflecting their vision about themselves and about the world. While providing the indigenous communities with video equipment, the project has stimulated image and information exchange among the nations. Initially the training of Indian video-makers was done village-by-village, providing records for their own use. Today, through national and regional workshops, they learn and discuss together ways to present their reality, for their own people and for the world.

Video in the Villages

Publication Date: 1987-2004Since the 1980s, the Video in the Villages' project has encouraged the encounter of the Amazonian Indians with their images. The project's proposal is to turn video into a tool that will enable the expression of their identity, reflecting their vision about themselves and about the world. While providing the indigenous communities with video equipment, the project has stimulated image and information exchange among the nations. Initially the training of Indian video-makers was done village-by-village, providing records for their own use. Today, through national and regional workshops, they learn and discuss together ways to present their reality, for their own people and for the world. -

Ringtone

by

Publication Date: 2017Welcome to the once-remote Aboriginal community of Gapuwiyak in northeast Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, where individual ringtones reveal rich insights into lives of the Yolngu people. From ancestral clan songs, animal calls and birdsongs to hip hop artists and gospel tunes, a Yolngu ringtone always comes with a great story. It might be the music a young woman dances to in a city nightclub, or a clan song invoking memories of ancestors and country. Yolngu people are renowned as first-rate storytellers with a keen sense of humour. In Ringtone, various individuals talk directly to camera as they reveal the advantages and perils of their new connectivity. Made collaboratively by Miyarrka Media, a new media arts collective of Indigenous and non-Indigenous filmmakers, Ringtone is a beautiful, funny and surprising film about the place of mobile phones in a contemporary Australian Aboriginal community.

Ringtone

by

Publication Date: 2017Welcome to the once-remote Aboriginal community of Gapuwiyak in northeast Arnhem Land in the Northern Territory of Australia, where individual ringtones reveal rich insights into lives of the Yolngu people. From ancestral clan songs, animal calls and birdsongs to hip hop artists and gospel tunes, a Yolngu ringtone always comes with a great story. It might be the music a young woman dances to in a city nightclub, or a clan song invoking memories of ancestors and country. Yolngu people are renowned as first-rate storytellers with a keen sense of humour. In Ringtone, various individuals talk directly to camera as they reveal the advantages and perils of their new connectivity. Made collaboratively by Miyarrka Media, a new media arts collective of Indigenous and non-Indigenous filmmakers, Ringtone is a beautiful, funny and surprising film about the place of mobile phones in a contemporary Australian Aboriginal community. -

Mandabi

by

Publication Date: 1968Recorded primarily in Wolof, this second feature by Ousmane Sembène was the first ever made in an African language--a major step toward the realization of the trailblazing Senegalese filmmaker's dream of creating a cinema by, about, and for the inhabitants of his home continent. After jobless Ibrahima Dieng receives a money order for 25,000 francs from a nephew who works in Paris, news of his windfall quickly spreads among his neighbors, who flock to him for loans even as his attempts to cash the order are stymied in a maze of bureaucratic obstacles, and new troubles rain down on his head. One of Sembène's most coruscatingly funny and indignant films, Mandabi--an adaptation of a novella by the director himself--is a bitterly ironic depiction of a society scarred by colonialism and plagued by corruption, greed and poverty.

Mandabi

by

Publication Date: 1968Recorded primarily in Wolof, this second feature by Ousmane Sembène was the first ever made in an African language--a major step toward the realization of the trailblazing Senegalese filmmaker's dream of creating a cinema by, about, and for the inhabitants of his home continent. After jobless Ibrahima Dieng receives a money order for 25,000 francs from a nephew who works in Paris, news of his windfall quickly spreads among his neighbors, who flock to him for loans even as his attempts to cash the order are stymied in a maze of bureaucratic obstacles, and new troubles rain down on his head. One of Sembène's most coruscatingly funny and indignant films, Mandabi--an adaptation of a novella by the director himself--is a bitterly ironic depiction of a society scarred by colonialism and plagued by corruption, greed and poverty. -

Selbe et tant d'autres

by

Publication Date: 1982Selbé et tant d’autres (Selbé: One Among Many; 1982) by Safi Faye (born 1943) begins how it ends. It is carried by song in a cycle that does not allow rest. In the documentary film’s first two minutes, we are introduced to Selbé, a thirty-nine-year-old mother of eight from Fad’jal, the filmmaker’s native Serer village in southern Senegal. We hear her doleful song, with a repeating lyric in Serer, “There is no respite for the unfortunate ones.” Her voice guides us throughout the thirty minutes of the film, as she sings at irregular intervals to accompany her labor. The lyrics reflect the film’s visual portrayal of her and other women at work and in constant motion in the absence of their husbands, who have migrated to the nearest cities in search of work.

Selbe et tant d'autres

by

Publication Date: 1982Selbé et tant d’autres (Selbé: One Among Many; 1982) by Safi Faye (born 1943) begins how it ends. It is carried by song in a cycle that does not allow rest. In the documentary film’s first two minutes, we are introduced to Selbé, a thirty-nine-year-old mother of eight from Fad’jal, the filmmaker’s native Serer village in southern Senegal. We hear her doleful song, with a repeating lyric in Serer, “There is no respite for the unfortunate ones.” Her voice guides us throughout the thirty minutes of the film, as she sings at irregular intervals to accompany her labor. The lyrics reflect the film’s visual portrayal of her and other women at work and in constant motion in the absence of their husbands, who have migrated to the nearest cities in search of work. -

Nice Coloured Girls

by

Publication Date: 1987This stylistically daring film audaciously explores the history of exploitation between white men and Aboriginal women, juxtaposing the “first encounter” between colonizers and native women with the attempts of modern urban Aboriginal women to reverse their fortunes. Through counterpoint of sound, image, and printed text, the film conveys the perspective of Aboriginal women while acknowledging that oppression and enforced silence still shape their consciousness.

Nice Coloured Girls

by

Publication Date: 1987This stylistically daring film audaciously explores the history of exploitation between white men and Aboriginal women, juxtaposing the “first encounter” between colonizers and native women with the attempts of modern urban Aboriginal women to reverse their fortunes. Through counterpoint of sound, image, and printed text, the film conveys the perspective of Aboriginal women while acknowledging that oppression and enforced silence still shape their consciousness. -

Itam Hakim Hopiit

by

Publication Date: 1985Recently inducted into the National Film Registry, Itam Hakim Hopiit, which translates as "we / someone, the Hopi," is a poetic visualization of Hopi philosophy. Made at the time of the Hopi Tricentennial - marking 300 years since the 1680 Pueblo Revolt against Spanish colonial rule – the film presents a view of Hopi culture and history. Speaking in Hopi, a community elder shares personal recollections and cultural history, recounting stories of the Hopi emergence, perseverance, and the Bow Clan migration stories of his father. Through use of the film medium, Masayesva challenges viewers to understand the Hopi conception of time as cyclic, in which the world starts, ends, and starts again.

Itam Hakim Hopiit

by

Publication Date: 1985Recently inducted into the National Film Registry, Itam Hakim Hopiit, which translates as "we / someone, the Hopi," is a poetic visualization of Hopi philosophy. Made at the time of the Hopi Tricentennial - marking 300 years since the 1680 Pueblo Revolt against Spanish colonial rule – the film presents a view of Hopi culture and history. Speaking in Hopi, a community elder shares personal recollections and cultural history, recounting stories of the Hopi emergence, perseverance, and the Bow Clan migration stories of his father. Through use of the film medium, Masayesva challenges viewers to understand the Hopi conception of time as cyclic, in which the world starts, ends, and starts again. -

Atanarjuat, The Fast Runner

by

Publication Date: 2001Atanarjuat is Canada's first feature-length fiction film written, produced, directed, and acted by Inuit. An exciting action thriller set in ancient Igloolik, the film unfolds as a life-threatening struggle between powerful natural and supernatural characters. Igloolik is a community of 1200 people located on a small island in the north Baffin region of the Canadian Arctic with archeological evidence of 4000 years of continuous habitation. Throughout these millennia, with no written language, untold numbers of nomadic Inuit renewed their culture and traditional knowledge for every generation entirely through storytelling. Atanarjuat is part of this continuous stream of oral history carried forward into the new millennium through a marriage of Inuit storytelling skills and new technology.

Atanarjuat, The Fast Runner

by

Publication Date: 2001Atanarjuat is Canada's first feature-length fiction film written, produced, directed, and acted by Inuit. An exciting action thriller set in ancient Igloolik, the film unfolds as a life-threatening struggle between powerful natural and supernatural characters. Igloolik is a community of 1200 people located on a small island in the north Baffin region of the Canadian Arctic with archeological evidence of 4000 years of continuous habitation. Throughout these millennia, with no written language, untold numbers of nomadic Inuit renewed their culture and traditional knowledge for every generation entirely through storytelling. Atanarjuat is part of this continuous stream of oral history carried forward into the new millennium through a marriage of Inuit storytelling skills and new technology.

Books about Ethnographic Cinema

-

The Ethnographer's Eye: Ways of Seeing in Anthropology by

ISBN: 0521773105Publication Date: 2001-04-23Grimshaw's exploration of the role of vision within modern anthropology engages with current debates about ocularcentism, investigating the relationship between vision and knowledge in ethnographic enquiry. Using John Berger's notion of 'ways of seeing', the author argues that vision operates differently as a technique and theory of knowledge within the discipline. In the first part of the book she examines contrasting visions at work in the so-called classical British school, reassessing the legacy of Rivers, Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown through the lens of early modern art and cinema. In the second part of the book, the changing relationship between vision and knowledge is explored through the anthropology of Jean Rouch, David and Judith MacDougall, and Melissa Llewelyn-Davies. Vision is foregrounded in the work of these contemporary ethnographers, focusing more general questions about technique and epistemology whether image-based media are used or not in ethnographic enquiry. -

Observational Cinema: Anthropology, Film, and the Exploration of Social Life by

ISBN: 0253354242Publication Date: 2009-11-17Once hailed as a radical breakthrough in documentary and ethnographic filmmaking, observational cinema has been criticized for a supposedly detached camera that objectifies and dehumanizes the subjects of its gaze. Anna Grimshaw and Amanda Ravetz provide the first critical history and in-depth appraisal of this movement, examining key works, filmmakers, and theorists, from André Bazin and the Italian neorealists, to American documentary films of the 1960s, to extended discussions of the ethnographic films of Herb Di Gioia, David Hancock, and David MacDougall. They make a new case for the importance of observational work in an emerging experimental anthropology, arguing that this medium exemplifies a non-textual anthropology that is both analytically rigorous and epistemologically challenging. -

The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography, and the Senses by

ISBN: 0691121559Publication Date: 2005-10-30In this book, David MacDougall, one of the leading ethnographic filmmakers and film scholars of his generation, builds upon the ideas from his widely praised Transcultural Cinema and argues for a new conception of how visual images create human knowledge in a world in which the value of seeing has often been eclipsed by words. In ten chapters, MacDougall explores the relations between photographic images and the human body-the body of the viewer and the body behind the camera as well as the body as seen in ethnography, cinema, and photography. In a landmark piece, he discusses the need for a new field of social aesthetics, further elaborated in his reflections on filming at an elite boys' school in northern India. The theme of the school is taken up as well in his discussion of fiction and nonfiction films of childhood. The book's final section presents a radical view of the history of visual anthropology as a maverick anthropological practice that was always at odds with the anthropology of words. In place of the conventional wisdom, he proposes a new set of principles for visual anthropology. These are essays in the classical sense--speculative, judicious, lucidly written, and mercifully jargon-free. The Corporeal Image presents the latest ideas from one of our foremost thinkers on the role of vision and visual representation in contemporary social thought. -

Transcultural Cinema by

ISBN: 0691012342Publication Date: 1998-12-27David MacDougall is a pivotal figure in the development of ethnographic cinema and visual anthropology. As a filmmaker, he has directed in Africa, Australia, India, and Europe. His prize-winning films (many made jointly with his wife, Judith MacDougall) include The Wedding Camels, Lorang's Way, To Live with Herds, A Wife among Wives, Takeover, PhotoWallahs, and Tempus de Baristas. As a theorist, he articulates central issues in the relation of film to anthropology, and is one of the few documentary filmmakers who writes extensively on these concerns. The essays collected here address, for instance, the difference between films and written texts and between the position of the filmmaker and that of the anthropological writer. In fact, these works provide an overview of the history of visual anthropology, as well as commentaries on specific subjects, such as point-of-view and subjectivity, reflexivity, the use of subtitles, and the role of the cinema subject. Refreshingly free of jargon, each piece belongs very much to the tradition of the essay in its personal engagement with exploring difficult issues. The author ultimately disputes the view that ethnographic filmmaking is merely a visual form of anthropology, maintaining instead that it is a radical anthropological practice, which challenges many of the basic assumptions of the discipline of anthropology itself. Although influential among filmmakers and critics, some of these essays were published in small journals and have been until now difficult to find. The three longest pieces, including the title essay, are new. -

Cine-Ethnography by

ISBN: 0816641048Publication Date: 2003-02-07One of the most influential figures in documentary and ethnographic filmmaking, Jean Rouch has made more than one hundred films in West Africa and France. In such acclaimed works as Jaguar, The Lion Hunters, and Cocorico, Monsieur Poulet, Rouch has explored racism, colonialism, African modernity, religious ritual, and music. He pioneered numerous film techniques and technologies, and in the process inspired generations of filmmakers, from New Wave directors, who emulated his cinema verité style, to today's documentarians.Ciné-Ethnography is a long-overdue English-language resource that collects Rouch's key writings, interviews, and other materials that distill his thinking on filmmaking, ethnography, and his own career. Editor Steven Feld opens with a concise overview of Rouch's career, highlighting the themes found throughout his work. In the four essays that follow, Rouch discusses the ethnographic film as a genre, the history of African cinema, his experiences of filmmaking among the Songhay, and the intertwined histories of French colonialism, anthropology, and cinema. And in four interviews, Rouch thoughtfully reflects on each of his films, as well as his artistic, intellectual, and political concerns. Ciné-Ethnography also contains an annotated transcript of Chronicle of a Summer--one of Rouch's most important works--along with commentary by the filmmakers, and concludes with a complete, annotated filmography and a bibliography.The most thorough resource on Rouch available in any language, Ciné-Ethnography makes clear this remarkable and still vital filmmaker's major role in the history of documentary cinema.Jean Rouch was born in Paris in 1917. He studied civil engineering before turning to film and anthropology in response to his experiences in West Africa during World War II. Rouch is the recipient of numerous awards, including the International Critics Award at Cannes for the film Chronicle of a Summer in 1961. Steven Feld is professor of music and anthropology at Columbia University. -

Principles of Visual Anthropology by

ISBN: 9783110179309Publication Date: 2003-08-13This edition contains 27 articles, written by scholars and filmmakers who are generally acknowledged as the international authorities in the field, and a new preface by the editor. The book covers ethnographic filming and its relations to the cinema and television; applications of filming to anthropological research, the uses of still photography, archives, and videotape; subdisciplinary applications in ethnography, archeology, bio-anthropology, museology and ethnohistory; and overcoming the funding problems of film production. -

The Cinematic Griot: The Ethnography of Jean Rouch

by

ISBN: 0226775461Publication Date: 1992-06-15The most prolific ethnographic filmmaker in the world, a pioneer of cinéma vérité and one of the earliest ethnographers of African societies, Jean Rouch (1917-) remains a controversial and often misunderstood figure in histories of anthropology and film. By examining Rouch's neglected ethnographic writings, Paul Stoller seeks to clarify the filmmaker's true place in anthropology. A brief account of Rouch's background, revealing the ethnographic foundations and intellectual assumptions underlying his fieldwork among the Songhay of Niger in the 1940s and 1950s, sets the stage for his emergence as a cinematic griot, a peripatetic bard who "recites" the story of a people through provocative imagery. Against this backdrop, Stoller considers Rouch's writings on Songhay history, myth, magic and possession, migration, and social change. By analyzing in depth some of Rouch's most important films and assessing Rouch's ethnography in terms of his own expertise in Songhay culture, Stoller demonstrates the inner connection between these two modes of representation. Stoller, who has done more fieldwork among the Songhay than anyone other than Rouch himself, here gives the first full account of Rouch the griot, whose own story scintillates with important implications for anthropology, ethnography, African studies, and film.

The Cinematic Griot: The Ethnography of Jean Rouch

by

ISBN: 0226775461Publication Date: 1992-06-15The most prolific ethnographic filmmaker in the world, a pioneer of cinéma vérité and one of the earliest ethnographers of African societies, Jean Rouch (1917-) remains a controversial and often misunderstood figure in histories of anthropology and film. By examining Rouch's neglected ethnographic writings, Paul Stoller seeks to clarify the filmmaker's true place in anthropology. A brief account of Rouch's background, revealing the ethnographic foundations and intellectual assumptions underlying his fieldwork among the Songhay of Niger in the 1940s and 1950s, sets the stage for his emergence as a cinematic griot, a peripatetic bard who "recites" the story of a people through provocative imagery. Against this backdrop, Stoller considers Rouch's writings on Songhay history, myth, magic and possession, migration, and social change. By analyzing in depth some of Rouch's most important films and assessing Rouch's ethnography in terms of his own expertise in Songhay culture, Stoller demonstrates the inner connection between these two modes of representation. Stoller, who has done more fieldwork among the Songhay than anyone other than Rouch himself, here gives the first full account of Rouch the griot, whose own story scintillates with important implications for anthropology, ethnography, African studies, and film. -

The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video by

ISBN: 9780429196997Publication Date: 2020-04-02The Routledge International Handbook of Ethnographic Film and Video is a state-of-the-art book which encompasses the breadth and depth of the field of ethnographic film and video-based research. With more and more researchers turning to film and video as a key element of their projects, and as research video production becomes more practical due to technological advances as well as the growing acceptance of video in everyday life, this critical book supports young researchers looking to develop the skills necessary to produce meaningful ethnographic films and videos, and serves as a comprehensive resource for social scientists looking to better understand and appreciate the unique ways in which film and video can serve as ways of knowing and as tools of knowledge mobilization. Comprised of 31 chapters authored by some of the world's leading experts in their respective fields, the book's contributors synthesize existing literature, introduce the historical and conceptual dimensions of the field, illustrate innovative methodologies and techniques, survey traditional and new technologies, reflect on ethics and moral imperatives, outline ways to work with people, objects, and tools, and shape the future agenda of the field. With a particular focus on making ethnographic film and video, as opposed to analyzing or critiquing it, from a variety of methodological approaches and styles, the Handbook provides both a comprehensive introduction and up-to-date survey of the field for a vast variety of audiovisual researchers, such as scholars and students in sociology, anthropology, geography, communication and media studies, education, cultural studies, film studies, visual arts, and related social science and humanities. As such, it will appeal to a multidisciplinary and international audience, and features a dynamic, forward-thinking, innovative, and contemporary focus oriented toward the very latest developments in the field, as well as future possibilities.